- The spread of coronavirus variants means COVID-19 will likely be around forever.

- People might require regular booster shots to fight new variants of the coronavirus.

- But experts caution that it’s impossible to vaccinate everyone in the world yearly, so the virus will continue to circulate.

- Visit the Business section of Insider for more stories.

As the pandemic approaches its second year, the coronavirus has morphed into a tougher foe than ever.

A number of mutations that scientists have identified in rapidly spreading variants are particularly worrisome. They raise concerns that these strains will be more contagious or be able to at least partly evade protection provided by vaccines and by prior infections.

Let’s be clear: No one knows how the next phase of the pandemic will play out. Is a future strain already spreading undetected or lurking around the corner? How effective will these vaccines be in the long run? And just when can we think about returning to schools and offices, or getting together with older relatives again?

Some of the nation’s top infectious-disease experts are hesitant to offer predictions.

“The first axiom of infectious disease: Never underestimate your pathogen,” Dr. Larry Corey, a virologist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, told Insider.

Despite this uncertainty, most scientists have accepted an unfortunate truth: The coronavirus will likely be part of our lives forever, though the pandemic phase will eventually come to an end. Our best hope is for it to turn into a mild, flu-like illness rather than a deadlier, long-term threat.

Here, we'll lay out the key factors that could determine which course the pandemic takes. Some of the most important unanswered questions hinge on what happens to variants next, and how well vaccinations and immunity can race to keep pace with them.

Read more: What's coming next for COVID-19 vaccines? Here's the latest on 11 leading programs.

Accept it: The coronavirus is here to stay

Getty Images

Four other human coronaviruses are already endemic in our population, meaning that they circulate perpetually but don't hit pandemic-level peaks. For the most part, these viruses cause only mild symptoms associated with common colds.

Scientists always feared a new coronavirus might come along that would be deadlier, yet still highly transmissible.

Enter our current virus: SARS-CoV-2.

"It's safe to say we're not going to eradicate it entirely," Dr. Becky Smith, an infectious disease specialist at Duke Health, said. "Too many people in the world have it. It's too efficient at transmitting."

The virus is also zoonotic, meaning it can jump back and forth between animals and humans. Even if we managed to eradicate SARS-CoV-2 in humans, animals could simply re-introduce a similar infection to our population - perhaps with an even deadlier mutation.

To this day, smallpox is the only infectious disease that has ever been eradicated in humans. It has no animal reservoir, so it must spread from human to human to survive.

A recent study suggested that SARS-CoV-2 would most likely become endemic within five to 10 years, eventually resembling a common cold that infects people during childhood. That scenario hinges on the notion that pediatric cases will remain mild. If a new mutation makes the virus deadlier in kids, coronavirus shots may become required for young people, similar to polio or measles vaccines.

Still, leading infectious disease expert Mike Osterholm said it's going to be nearly impossible to make a yearly coronavirus vaccine available to every person on Earth.

"It is going to be with us forever," Osterholm, who directs of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota, said of the virus. "It is something we can't eradicate from humans."

New variants are forcing vaccine-makers to change strategies

Pedro Vilela/Getty Images

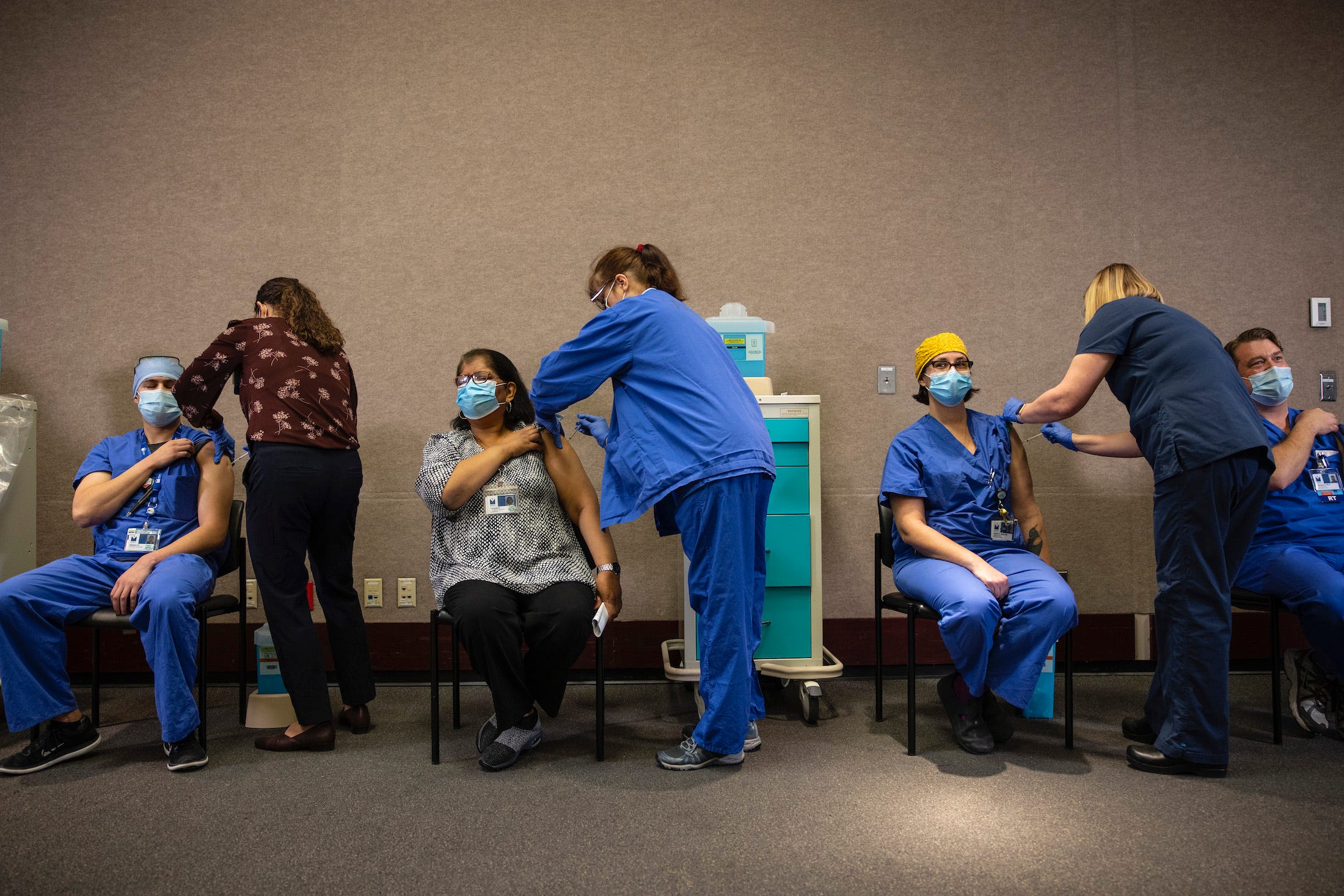

When the first vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna were authorized for emergency use last year, there was real hope they could crush the pandemic. The shots were over 90% effective - a stunning achievement - and provided overwhelming protection against mild, moderate, and severe symptoms.

Now, the goal for vaccines has become more modest: simply to blunt the worst outcomes, preventing deaths and hospital stays.

"I've seen the language changing already from 'We're going to hit herd immunity' to 'Hey, we're going to have something that is going to get us back to normal, from the perspective that our hospitals aren't going to be overloaded,'" Deborah Fuller, a microbiologist and vaccine researcher at the University of Washington, said.

That's partly due to concern about a new variant, called B.1.351, circulating widely in South Africa. The strain carries 10 mutations in the virus' spike protein - the biological target of all the leading vaccine programs. The P.1 strain circulating in Brazil has similarly troubling mutations.

B.1.351 has already shown partial resistance to Moderna's vaccine, suggesting the shot may be less effective at preventing milder illnesses caused by this strain. Early clinical results from vaccine programs led by Johnson & Johnson, AstraZeneca, and Novavax have also raised concerns that vaccines won't work as well against B.1.351 or other variants with similar mutations.

The quality of these findings is still up in the air: Some laboratory work in petri dishes has been published, but no results from tests in people have appeared in medical journals.

Vaccine research is just getting started

Jack Guez/AFP via Getty Images

Still, even if vaccines don't work quite as well against some new coronavirus strains, that "doesn't mean these vaccines are useless," Brian Ward, medical officer of vaccine developer Medicago, told Insider.

Vaccines remain humanity's best weapon against the coronavirus - and they are already being updated in an attempt to stay ahead of it.

Moderna and Novavax are going forward with plans for booster shots tailored to protect against the B.1.351 strain. Pfizer and J&J are monitoring the pandemic to pick the right strains to target next.

All told, it seems likely that the most vulnerable people in wealthy countries will get at least one booster shot. Companies haven't said when booster shots might be ready, but if the B.1.351 variant spreads rapidly in the US and elsewhere, SVB Leerink biotech analyst Geoffrey Porges said he thinks booster shots could start rolling out as soon as late spring or early summer.

Next-generation vaccines are in the works at dozens of drug companies. Some of these aim to neutralize multiple coronavirus variants while other programs are starting to develop a combination vaccine to protect against the flu and COVID-19.

Will the virus keep drifting away from original strains?

Boris Roessler/picture alliance via Getty Images

It's possible more powerful, infectious variants could drown out old versions of the virus, making the pandemic harder to combat. Virus experts in the US are already projecting that the fast-spreading B.1.1.7 variant of the virus, first discovered in the UK, will likely become the dominant form of COVID-19 in America by this March.

But it's impossible to predict what changes the virus might undergo next, or what they'll really mean for us. After all, not all mutations make viruses more dangerous.

"Maybe the virus will change and become less contagious," said Dr. Cody Meissner, a respiratory virus expert at Tufts Medical Center. "Maybe it will begin to cause less severe disease, because - remember - a virus doesn't want to kill its host."

Another possibility is that the current variants may be about as troubling as it gets. Some virologists believe the virus, after infecting hundreds of millions of people, has already reached a high level of fitness, meaning it won't evolve much more.

One thing remains certain: the best defense against new variants is stopping transmission from person to person. More widespread vaccinations could lend a hand in that regard.

If we don't vaccinate the whole world, unvaccinated people will keep circulating the virus - and the virus, in turn, will keep changing on its own terms.

Is recovering from COVID-19 enough to be immune from new variants?

Angela Weiss/AFP/Getty Images

Another troubling pair of questions centers on the body's natural defenses against the coronavirus. Researchers are studying how long this protection lasts, and whether people who've been infected once could be vulnerable to new infections from variants.

Researchers have found that coronavirus antibodies - blood proteins that protect the body from subsequent infection - fade within a few months. Other layers of immunity may last longer and protect people from emerging strains.

White blood cells known as T cells and B cells also remember foreign invaders, often for longer periods of time than antibodies. A recent study suggested that recovered coronavirus patients had robust T-cell and B-cell immunity for at least eight months. A study of SARS, which is caused by a similar coronavirus, showed that recovered patients had T-cell protection 17 years after their infection.

Researchers do expect that infections will be milder the second time around, based on how other human coronavirus behave. But a reinfected person could still spread the virus around.

New variants complicate the matter further, since most studies of coronavirus immunity haven't considered strains like B.1.351. A recent study found that B.1.351 infections were just as common among people who'd previously recovered from COVID-19 as those who had not.

Under the worst-case scenario, the immune systems of people who've had COVID-19 wouldn't recognize new variants at all. An October study in The Lancet, for instance, identified a 25-year-old man who was reinfected with a new variant in June that produced more severe symptoms than his first illness in April.

Jennie Lavine, a postdoctoral researcher at Emory University said she still thinks that leading coronavirus vaccines will offer some protection.

When it comes to other viruses like varicella-zoster (the virus responsible for chickenpox), Smith added, vaccines are sometimes even better than natural immunity. People who get the chickenpox vaccine as children are 20 times less likely to get shingles as adults, she said.

It's possible people vaccinated against COVID-19 will get better protection from the virus than those who were previously infected.

Basic COVID-19 precautions still matter, perhaps now more than ever

Paula Bronstein/Getty Images

We don't know exactly why or how new variants spread so well, so making sure people are masked, distanced, and washing their hands is as critical as ever.

Treatments for the virus - especially in its early, mild stages - are still elusive. That may remain the case for quite a while. We still don't have good treatments for many other viruses, including polio, measles, mumps, and rubella. Instead, we rely on vaccinations to prevent them.

"This virus is something that we're going to learn to live with, just as we do with influenza," Meissner said.

"What we really want to do is stop the hospitalizations, stop the deaths."

Dr. Catherine Schuster-Bruce contributed reporting.