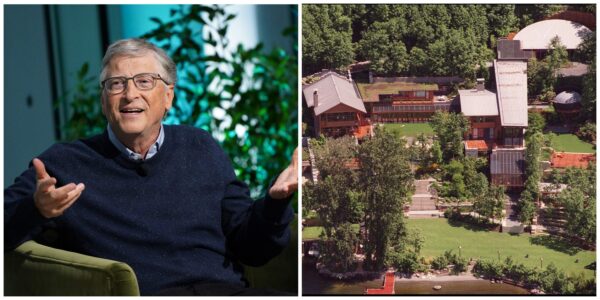

- On Monday, Netflix released “The Devil Next Door,” a five-part docuseries about John Demjanjuk, a naturalized US citizen who was accused of being a guard at a Nazi death camp.

- The case was full of twist of turns. After initially being convicted of crimes against humanity in Israel, he was acquitted just a few years later. But then he was extradited from the US to stand trial in Germany.

- Demjanjuk, who was initially believed to be the notorious death camp guard “Ivan the Terrible,” died in Germany while appealing his case in 2012.

- Visit Insider’s homepage for more stories.

The dramatic case of John Demjanjuk, a naturalized citizen who was accused of being a Nazi death camp guard, is the subject of a much-talked-about new Netflix docuseries.

“The Devil Next Door” premiered Monday on the streaming service, and focuses mostly on Demjanjuk’s trial in Israel in the 1980s – one of the last major Nazi war crimes trials.

The emotional trial, attended by many Holocaust survivors, led to an even more dramatic acquittal just a few years after he was sentenced to hang, when new evidence cast doubt on the accusations against him.

But Demjanjuk’s freedom was short-lived. He was deported from the US for a second time in his life in the late aughts to face trial again, this time in Germany.

Here's the history behind this still-mysterious case that inspired the series.

On Monday, Netflix released "The Devil Next Door," a five-part docuseries on John Demjanjuk, a naturalized American citizen accused of being a notorious Nazi death camp guard.

Critics' reviews are mixed, and it has an 80% audience score on Rotten Tomatoes.

In 1986, Demjanjuk was deported to Israel to face trial for his alleged war crimes, after the Justice Department uncovered evidence suggesting that he worked at the Treblinka death camp where 870,000 people were killed during the Holocaust.

John Demjanjuk was born Ivan Demjanjuk on April 3, 1920 in Debovye, Ukraine, The New York Times reported. In 1941, he was conscripted into the Soviet Army, but wounded and captured by the Germans just a year later.

Just how he spent the wartime years has never been totally confirmed. After the war, he met his wife Vera in a German camp for displaced persons, and the two emigrated to the US in 1952, settling in Cleveland, Ohio. Demjanjuk changed his first name to John and went to work at a Ford factory. The couple went on to have three children.

According to Refinery 29, Demjanjuk first came onto American authorities' radar in 1974, when an American journalist of Ukrainian descent, Michael Hanusiak, traveled to the Soviet Union and received a list of suspected Nazi collaborators who had since become American citizens.

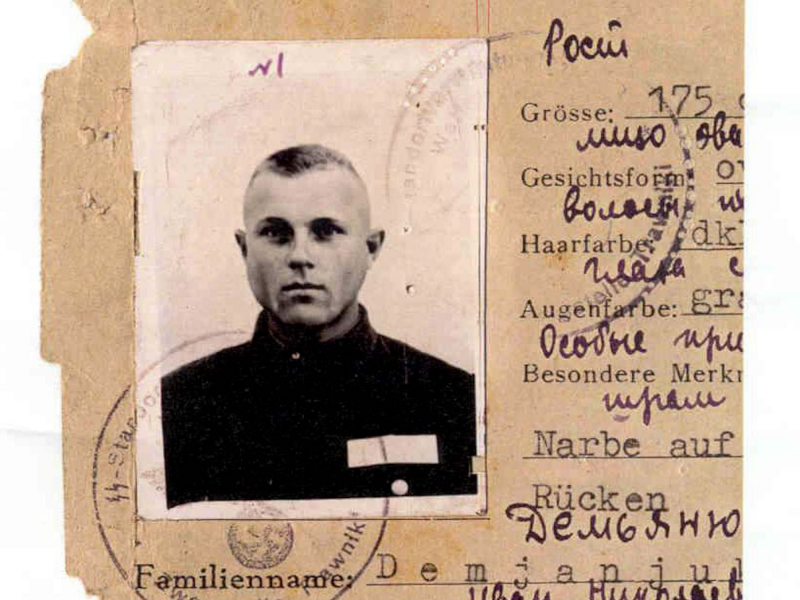

While investigating another person on the list, Holocaust survivors recognized Demjanjuk's ID photo from that era and said he was "Ivan the Terrible," a notoriously cruel guard who operated the gas chambers at Treblinka.

On the basis that he had lied about his death camp work on his immigration application, Demjanjuk was stripped of his citizenship in 1981, and extradited to Israel to stand trial five years later.

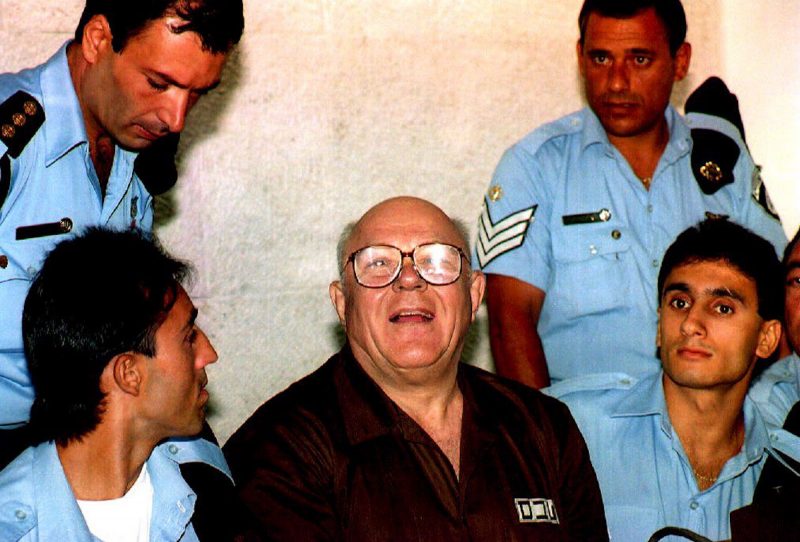

The trial against Demjanjuk wrapped up in 1988, after a year-and-a-half. The now 68-year-old was found guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced to death.

During the trial, prosecutors said Demjanjuk volunteered to work in the camps, where he ran the engines that fueled the gas chambers, making him directly responsible for the killing of thousands of people between 1942 and 1943.

Demjanjuk said he spent most of the war as a prisoner, and that the Nazis forced him to work the camps.

Holocaust survivors testified about Ivan the Terrible's sadistic behavior at Treblinka, saying he seemed to take pleasure in beating prisoners with a steel pipe and cutting off their limbs with a sword.

Particularly emotional testimony came from then 65-year-old Eliyahu Rosenberg who, when asked if he could identify the defendant, asked Demjanjuk to take off his glasses so he could see his eyes. He then went up to Demjanjuk and said there was no "shadow of a doubt" that he was "Ivan from Treblinka".

"I saw his eyes, I saw those murderous eyes,'' Rosenberg said, according to the Chicago Tribune.

Demjanjuk's defense team called into question the reliability of these stories, since they were decades old. And they pointed to holes in the prosecution's story, such as the fact that Demjanjuk's ID did not mention his work at Treblinka, only the other camps of Chelmno and Sobibor. They also said there was evidence on the ID card that it had been tampered with, and that the photo may have been lifted from somewhere else.

Nonetheless, he was found guilty of crimes against humanity in 1988 and sentenced to be hanged.

Five years later, the Israeli Supreme Court overturned Demjanjuk's conviction and he was freed. His American citizenship was restored and he returned to his family in Cleveland, Ohio.

The Soviet Union fell while Demjanjuk was appealing his case, which led his legal team to uncover some KGB files on Nazi war criminals that suggested he may have been confused with another death camp guard.

The Soviets collected the testimonies of 37 former Treblinka guards who said that the real name of Ivan the Terrible was Ivan Marchenko, who they identified in photos that bore little resemblance to Demjanjuk, The New York Times reported at the time.

Despite the fact that there was plenty of evidence that Demjanjuk worked at the Sobibor death camp, the only witness who could corroborate this had died and could no longer be cross-examined, according to The Jerusalem Post. So the Israeli Supreme Court decided to overturn the conviction and let Demjanjuk go free.

Demjanjuk was stripped of his citizenship a second time in 2004, and five years later deported to Germany to stand trial for war crimes there.

Demjanjuk was eventually allowed to return to his family in Cleveland, where a federal appeals court overturned his 1981 conviction. His US citizenship was restored in 1998, The New York Times reported.

But his happiness was short-lived. A year later, the Justice Department's Nazi hunting division (the Office of Special Investigations) sued to have Demjanjuk's citizenship revoked a second time, this time based on his work at Sobibor.

Demjanjuk took the case to trial, and in 2004 an appeals court confirmed the decision, making Demjanjuk stateless for a second time in his life.

As Demjanjuk was deported a second time in 2009, his wife Vera held onto her granddaughter Olivia Nishnic for support.

The couple had one son, two daughters, seven grandchildren, and two great-grandchildren, according to The New York Times.

A German court found Demjanjuk guilty of accessory to murder in May 2011 and sentenced him to five years in prison.

Germany eventually agreed to accept Demjanjuk so that he could go on trial for murder there in 2009, The New York Times reported. Demjanjuk tried to fight standing trial since he was ill with kidney and bone marrow disease, but doctors said he was healthy enough. He often attended his court appearances in a wheelchair or on a stretcher.

While there was no hard evidence that Demjanjuk killed anyone at the camp, the prosecution based their case on the fact that any guard working at a death camp was at least an accessory to murder, according to The Jerusalem Post.

That argument worked, and in May 2011, at the age of 91, Demjanjuk was found guilty of being an accessory to the murder of 28,060 Jews at Sobibor and sentenced to five years in prison, The Guardian reported.

He died while awaiting appeal less than a year later, in March 2012.

Demjanjuk received a credit of two years of pretrial detention, so only had to serve three, The New York Times reported.

But he was allowed to stay at a nursing home pending his appeal. He died at that nursing home at little less than a year later, in March 2012.