- The Hague Institute for Innovation of Law is a nonprofit based in The Hague, Netherlands.

- Its work focuses on injustices such as people getting kicked off their land or losing their job.

- It surveys people about pressing justice issues and supports entrepreneurs trying to solve them.

- This article is part of the "Financing a Sustainable Future" series exploring how companies take steps to set and fund sustainable goals.

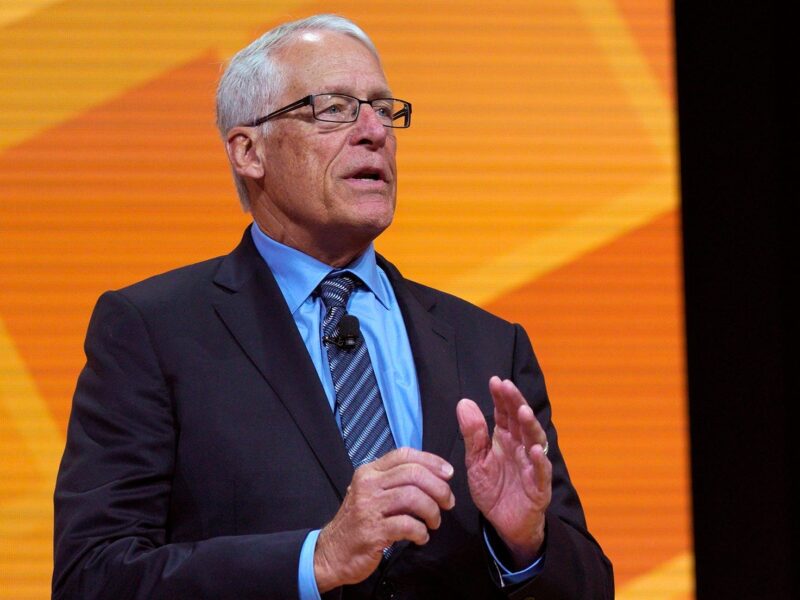

In 2004, Sam Muller was a lawyer helping build the International Criminal Court in The Hague, Netherlands, where people accused of war crimes and genocide are tried. It was the kind of work he'd always dreamed of doing. Then, he said, "something odd" happened to him.

Muller told Insider that during his travels around the world, he "had seen so much 'ordinary justice' go wrong." Ordinary justice, as Muller sees it, involves people's ability to work, to support their family, or simply to live safely. He'd seen people get kicked off the land they owned and others lose their jobs unfairly.

These infractions, Muller said, tended not to draw the attention of lawmakers and policymakers. But they had profound effects on people's livelihood and well-being. In 2005, this realization prompted Muller to found the Hague Institute for Innovation of Law, or HiiL, a nonprofit headquartered in The Hague that today has 44 staff members and donors like the European Union and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The institute researches justice issues worldwide while identifying and supporting the social entrepreneurs meeting those needs in local markets. It says some 139 startups have participated in its Justice Accelerator program to address justice issues, with 84 of them in operation as of 2021.

It also runs events such as the annual World Justice Forum, which kicks off on May 30, with speakers including Sherrilyn Ifill, the president and director-counsel emeritus of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and Mary Robinson, the chair of The Elders, the global leadership organization founded by Nelson Mandela.

It's about making global justice efforts more local and more agile.

"I wanted to step out of the rather cumbersome, complex, sometimes bureaucratic UN, even though it did a lot of good stuff, and find a more dynamic environment," Muller said.

He added that creating that environment fits into a broader goal of building a sustainable society. "One of the things that justice systems do is they allow societies to keep their trust, to keep their social cohesion," he said.

HiiL's research suggests that injustices related to family, work, and land are among the most pressing

The institute's approach to user-friendly justice involves identifying problems and testing solutions.

Through surveys of populations across the globe, it has found that the injustices that bother most people have to do with family, work, land, public services, and crime. It has published research on the state of justice and how citizens feel served by their justice systems in Nigeria, Syria, and the United States, among other countries.

It runs "Justice Needs and Satisfaction" surveys on a national scale and then convenes entrepreneurs who can tackle the problems.

The institute looks to partner with organizations developing tools to help people resolve injustice on their own. Justice Accelerator alums include We Are More, a digital legal-aid platform in Kenya, and Molao365, a free legal-advice service in South Africa. Housing was identified as an issue in America, so the institute supported a startup called JustFix that wants to make it easy for New York City renters to research property owners, put in requests for repairs, and protect themselves from eviction.

The institute has also worked with the international law firm Clifford Chance on promoting equal access to justice in Africa and with the information-services firm Wolters Kluwer on mentoring entrepreneurs.

HiiL communicates the impact of its work through stories and statistics

The institute sometimes draws on the stories of people who have experienced injustice — as people tend to remember stories better than facts and numbers — but more often uses data and statistics to show how widespread injustice is.

Muller said that "it's very important to be in touch with the real stories and the lives" that injustice affects. "At the same time, you can't get stuck in that," he said. "You've got to make it something that somebody who works on policy or strategy can actually work with."

To that end, its leadership tries to quantify the impact of its work in ways that make sense to both the public and potential investors. In a 2021 policy brief, the institute reported on an economic-advice agency's finding that resolving or preventing 80% of ordinary injustices in the Netherlands would yield a roughly 0.15% contribution to the country's gross domestic product. It said the agency found that every $1 invested in achieving user-friendly justice translated to a $14 gain in productivity and $10 saved in the cost of public services.

Ultimately, Muller thinks building a user-friendly justice system will require his team to keep adapting. "It's a big, wicked problem," he said.