- Millions of tons of plastic accumulate in the oceans each year, but only a small fraction of that winds up on the surface.

- For years, scientists believed that the “missing” plastic quickly degraded into tiny fragments, then fell to the bottom of the ocean.

- A new study from The Ocean Cleanup, a nonprofit founded by Boyan Slat, 25, challenges that theory.

- The study found that plastics undergo a long journey toward areas like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a trash-filled vortex that’s more than twice the size of Texas. Along the way, plastic either gets pushed back toward land or sinks beneath the surface of the water.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

About 8.8 million tons of plastic accumulate in the oceans each year, but only about 270,000 tons are believed to be floating on the surface.

For years, most scientists have thought that the “missing” plastic quickly degrades after entering the ocean, breaking apart into microplastics – tiny fragments less than 5 millimeters long – then falling to the bottom of the ocean.

But this theory is inconsistent with observations made by researchers at The Ocean Cleanup, a nonprofit that aims to rid the oceans of plastic. The organization was founded in 2013 by Boyan Slat, an entrepreneur, who was just 19 years old at the time. Slat, now 25, is inching closer toward his goal of cleaning up the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, a trash-filled ocean vortex that’s more than twice the size of Texas.

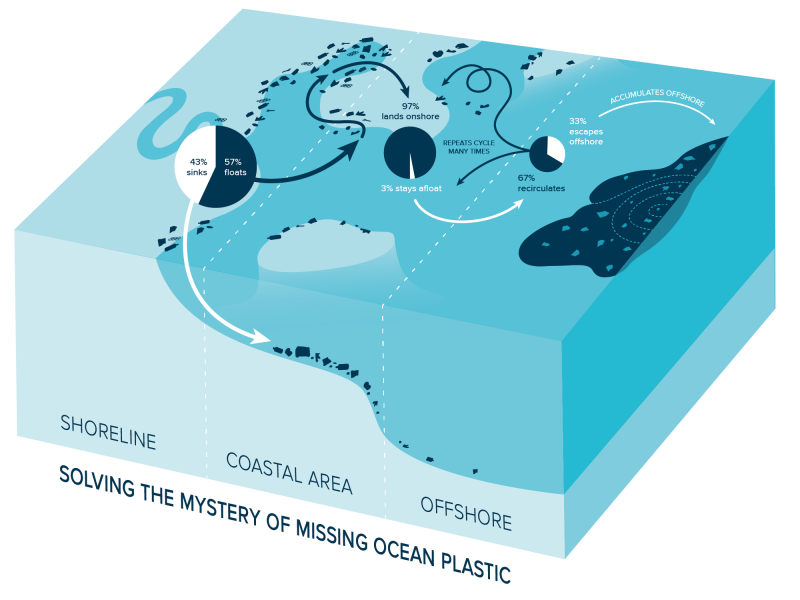

On Thursday, The Ocean Cleanup released a study that offers an alternative explanation for why certain plastic items sit on the surface of the water while others go missing. Rather than quickly dissolving into microplastics, plastic objects get repeatedly pushed back toward land or disappear underneath the surface of the water, the team found.

"It is quite a contrarian view," Slat told Business Insider. "I think we've been able to answer, or at least allude to, the biggest knowledge gap in the area of plastic pollution."

'We don't really find any plastic bags or straws'

Over the past several years, Ocean Cleanup researchers have noticed that a specific type of plastic accumulates in the garbage patch.

"A lot of it is really weathered and broken down, and some of it looks really old," Laurent Lebreton, the study's lead author, told Business Insider. "We don't really find any plastic bags or straws, but we find really thick, hard plastic fragments."

The researchers found that majority of the items they retrieved from the garbage patch in 2015 were from the 2000s, and some were much older. This suggested that plastic objects were not disintegrating very quickly.

"It's really quite shocking to see pieces of plastic still floating out there that are from the 1970s," Slat said. "Just a few weeks ago, we recovered a crate that's literally from 1970 from Japan."

The researchers concluded that instead of breaking down, plastic objects embark on a long journey, sometimes traveling for decades, before accumulating in large offshore patches.

Plastic's journey through the ocean

A small share of plastic in the ocean comes from illegal dumping, spills at sea, or production facilities that release plastic debris into nearby waterways. But most of it comes from litter on land.

Plastic waste that enters the ocean sometimes accumulates along coastlines where no humans are around to scoop up trash. An example of this, Lebreton said, is Australia's Cocos Islands, a remote area with few residents that has the highest density of plastic debris reported anywhere on Earth (about 260 tons). On those shores, large amounts of plastic get swept away by the tide, then carried back to the same location.

This cycle ends with the plastic degrading or making its way offshore.

Less than 1% of the plastic that enters the ocean from the shore actually makes its way to a gyre like the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the researchers found.

As a plastic object travels through the ocean, organisms like algae or barnacles attach to it and start to weigh it down - a process known as "fouling." The object then sinks below the surface, toward deeper parts of the ocean.

Algae and barnacles require sunlight to survive, however, and that becomes scarce as they sink deeper with their plastic home. Eventually, the organisms may die and fall off the plastic object, allowing it to rise back to the surface.

Lebreton said thick pieces of plastic often resist the weight of organisms, while thin pieces tend to lose their buoyancy. That explains why there aren't many flimsy straws or plastic bags in the garbage patch, he said.

The researchers found that thin plastic pieces could spring back to the surface in deep water, but in shallower water they're more likely to land on the bottom and stay there.

Cleaning up the Great Pacific Garbage Patch

Eventually, the plastic that winds up swirling in offshore vortexes does degrade, but it can take a while. The researchers found that most plastic objects that are now disintegrating into microplastics were produced in the 1990s or earlier. When a plastic object degrades, the resulting microplastics tend to rain down like ash toward the bottom of the ocean.

Lebreton said that without any intervention, trash in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch could take several decades - if not centuries - to disintegrate.

"If you stopped putting plastic into the ocean, or just in the natural environment in general, you'd still have to deal with the legacy of plastic waste," he said. "In that sense, we can really say the worst is yet to come."

Slat said the new study "confirms the strategy" of The Ocean Cleanup, since solving the plastic-pollution problem requires both prevention (such as recycling efforts on land) and cleaning up the plastic already in the water.

Slat's solution is a floating, U-shaped array that captures plastic in its fold like a giant arm. The device moves slower than the ocean's current thanks to an underwater parachute that serves as an anchor. As wind and waves push plastic toward the center of the U-shaped system, the debris is captured by a screen that extends beneath the surface. The collected trash can then be towed to shore on a vessel.

If successful, The Ocean Cleanup says, its device could cut the size of the garbage patch in half over five years.

"To me, it's not really a question of whether it's going to work - it's when it's going to work," Slat said. "I don't think we have a choice, considering the scale of the problem."