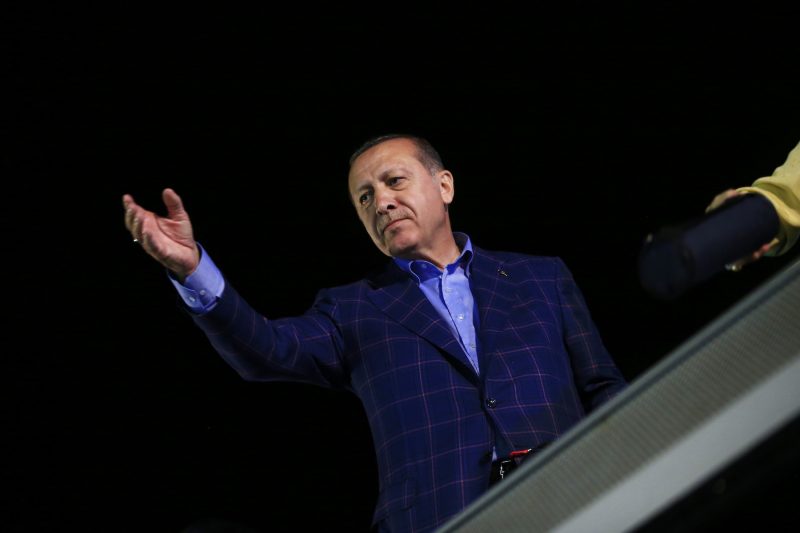

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan won a narrow victory Sunday in a referendum that will allow him to vastly expand his presidential powers less than a year after a botched coup attempt failed to unseat him and cemented his party’s grip on power.

In a nationwide vote, just over 51% of Turkish citizens elected to change Turkey’s constitution to create an executive presidency for the first time in the country’s modern history. Nearly 49% voted against the change.

“Though the opposition is still disputing the final vote tallies, the Turkish public seems to have given Erdogan and the AKP [Justice and Development Party] license to reorganize the Turkish state and in the process raze the values on which it was built,” Steven A. Cook, asenior fellow for Middle East & Africa studies at the Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), wrote on Sunday.

The vote was ruled valid by Turkey’s electoral body on Monday morning. But the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, which monitors elections, said that the vote was held on an “unlevel playing field” because of intimidation campaigns against “no” voters, Erdogan’s war on the free press, and non-stamped ballots whose legitimacy have been called into question.

Still, it seems unlikely that the referendum would be held again. And many now fear that its result – which, among other things, will abolish the office of the prime minister that Erdogan held for 10 years before becoming president in 2014 – will allow Erdogan to continue his relentless crackdown on “terrorist sympathizers” and suspected followers of Fethullah Gulen.

Gulen, a Pennsylvania-based cleric who Erdogan has accused of organizing the botched coup and generally fomenting unrest in Turkey, has denied any involvement.

"The powers that would be afforded to the executive presidency are vast, including the ability to appoint judges without input from parliament, issue decrees with the force of law, and dissolve parliament," Cook wrote.

"The president would also have the sole prerogative over all senior appointments in the bureaucracy and exercise exclusive control of the armed forces."

Turkey has the second-largest military in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and partnered with the US-led anti-ISIS coalition in mid-2015 amid pressure to crack down on the terror group, which had been operating with virtual impunity on its southern border. It is unclear how Erdogan, who now has more power and less of a need for legitimacy from the West, will direct Turkey's military might.

"The Turkish Republic has always been flawed," Cook said. "But it always contained the aspiration that - against the backdrop of the principles to which successive constitutions claimed fidelity - it could become a democracy. Erdogan's new Turkey closes off that prospect."

Erdogan 'will have to act differently from other dictators'

Some experts have said the close outcome of the referendum is a signal of the widespread and deep-seated nature of Turkey's opposition. Nine months into a brutal government purge, in which nearly 50,000 people have been arrested, Erdogan still fell far short of garnering the kind of popular support he craves.

"Erdogan is wary about the fact that he failed in swaying half the Turkish electorate his way despite the brutal crackdown and scandalously unfair campaign under nine-month-long state of emergency," said Aykan Erdemir, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and former member of Turkish parliament.

"This is why he will have to act differently from other dictators in the Middle East, and allow a relatively wider sphere of action for the opposition," he added.

Erdemir said that while Turkey's parliamentary democracy "has been replaced by one-man rule in the guise of a centralized presidency," Erdogan "still has a long way to go before he can obliterate fully the secular republican underpinnings of the regime."

Soner Cagaptay, a Turkey expert at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, largely echoed that assessment in an interview with The Washington Post.

"I think it's actually the 'best' outcome," Cagaptay said. "If Erdogan had lost, this would have unleashed a period of instability as he would have gone for a rerun of the vote as many analysts predicted he would, and if he had won with a wide margin, he would 'gone off the charts,' becoming completely authoritarian. Now, his wings have been clipped and he has been humbled."

He added: "This is the crisis of Turkey now: Erdogan has become the most powerful Turk, but while half of the country adores him, the other half loathes him."

But others say the creation of an executive presidency, which expands term limits and would allow Erdogan to stay in office until 2029, will have concerning geopolitical consequences. The constitutional change has cemented the ruling Justice and Development Party's grip on power, experts say, which will in turn hasten the NATO member's drift away from Europe.

The AKP "harnessed anti-Westernism during the [referendum] campaign to galvanize public support in favor of constitutional reforms to the presidency that would, according to the AKP, increase stability, stave off future political crises, and reduce external meddling in Turkish affairs," Aaron Stein, a resident senior fellow at the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East, wrote last weekend.

"This message builds on a rash of conspiracy theories levied against the United States and, to a lesser extent, European states surrounding their alleged involvement in last year's failed coup attempt," Stein added.

While both the European Union and Ankara have kept Turkey's bid to join the EU alive, it is on life support, Stein said - and closer to death than ever.

"The truth is that electoral dynamics in both Europe and Turkey are pushing the two sides apart," he wrote. "The referendum simply magnified what was obvious."

Ian Bremmer, president of the political risk firm Eurasia Group, said that while the "top headlines" from Turkey's referendum vote "will be a European country turning to authoritarianism, there's less shock value in that these days - not only from Turkey, whose political descent has been coming for years now, but also from their neighbors across east and southeast Europe."

"It's less about critical instability," Bremmer added, "than no longer knowing what 'Europe' stands for."