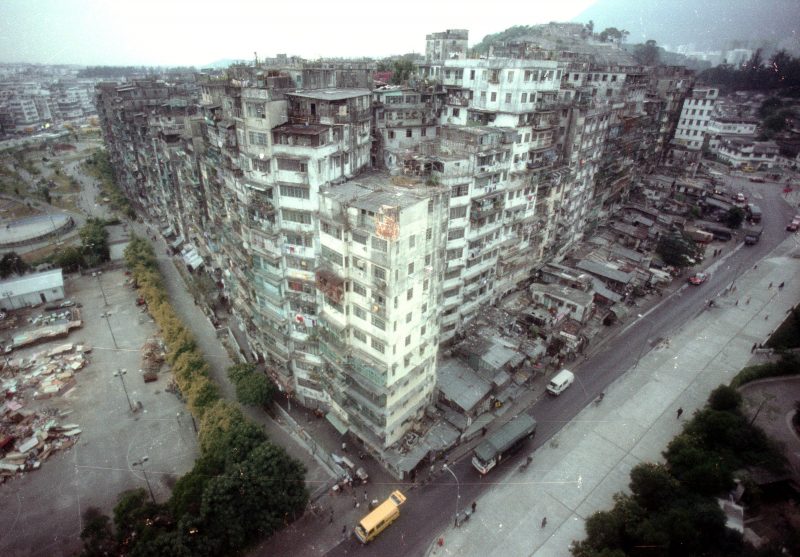

Between the 1950s and mid-1990s, tens of thousands of immigrants constructed a towering community 12 stories high across a 6.4-acre lot in Hong Kong.

It was called the Kowloon Walled City.

With a population of 33,000 squeezed into a tiny lot, the city at its peak was 119 times as dense as present-day New York City. Although it faced rampant crime and poor sanitation, the city was impressively self-sustainable until its demolition in 1993.

In the late ’80s, the Canadian photographer Greg Girard found his way into the windowless world.

He shared photos and thoughts about his time in Kowloon Walled City with Business Insider. You can check out the rest, along with essays and work from photographer Ian Lambot, in “City of Darkness: Revisited.”

Though Hong Kong had been under British rule for decades by the time construction began, a clause in an 1842 treaty meant China still owned the property that would become Kowloon. Caught in legal limbo, it was effectively lawless.

By 1986, the Walled City had caught the attention of photographer Greg Girard. Girard would spend the next four years in and out of the city, capturing daily life inside its teetering walls.

The Lego-like city was built over decades, as residents simply stacked rooms one on top of another. The end result "looked formidable," Girard tells Business Insider, "but who knows?"

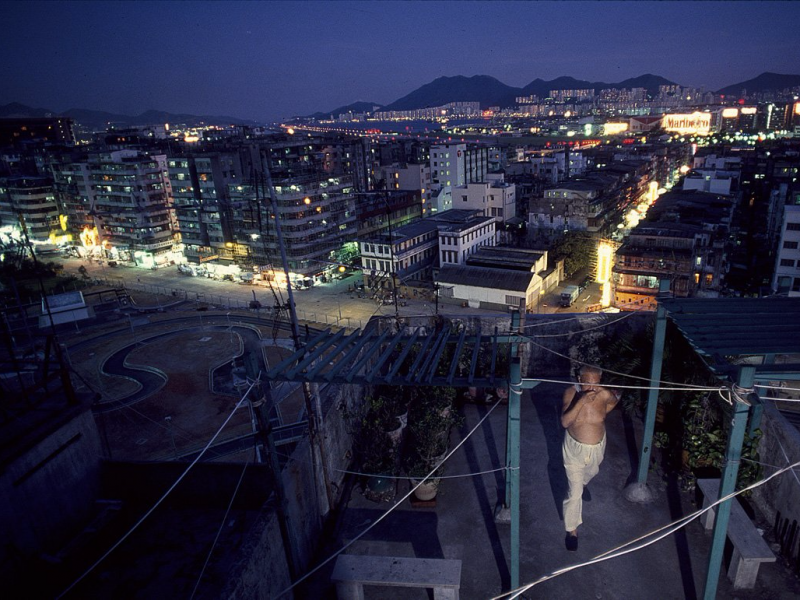

At night, the city's lawlessness became truly apparent. Crime was rampant, and anyone who knew better wouldn't trespass near the city's walls.

Even though the area wasn't terribly dangerous by the time Girard visited, he says local children were still told by their parents not to go near Kowloon.

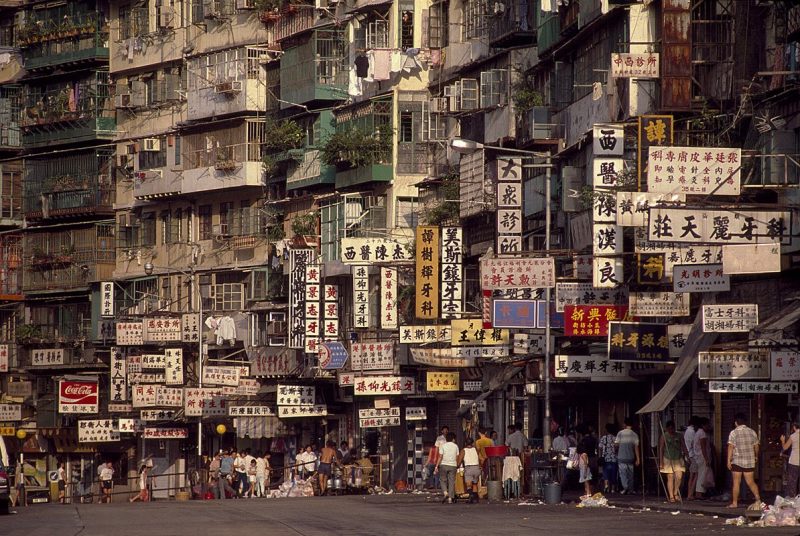

Kowloon offered just about every business imaginable, for better or worse. At night, schools and salons were converted into strip clubs and gambling halls. Trafficked drugs — mostly opium — made frequent appearances.

One woman, Wong Cheung Mi, worked as a dentist.

Like many of the Walled City's dentists, Wong could not practice anywhere else in Hong Kong. This drew hordes of working-class citizens to visit the city just to receive affordable healthcare and services.

Stacked housing blocks meant virtually no sunlight could pierce through. Even during the day, Girard says, "it was nighttime all the time in there."

The one place of respite from the dampness was on the roof, though Girard says this was the most unsafe of all: "There were a lot of additional things sticking out and spaces between buildings that had been combined."

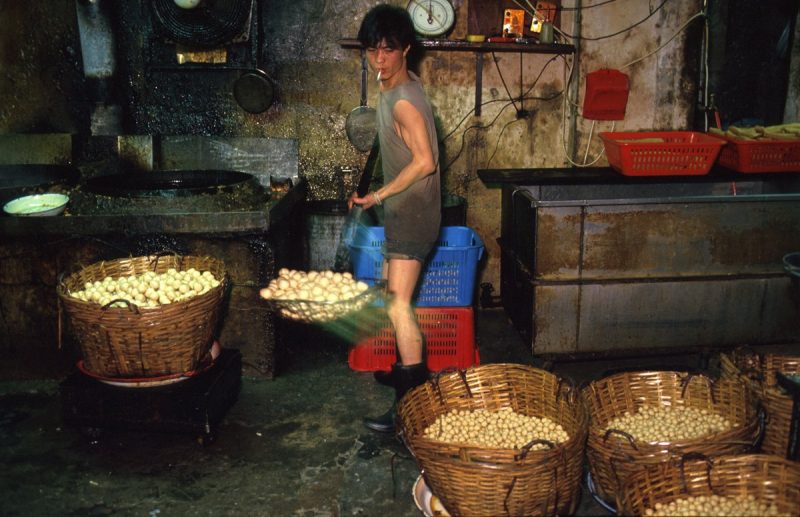

In-house manufacturing was a huge part of the Walled City's infrastructure. Dog-meat butchers, entrepreneurs, and noodle makers enjoyed zero oversight inside the walls.

Hui Tuy Choy opened his noodle factory in 1965, totally free to ignore health, fire, and labor codes.

Some of the most common products manufactured in the city were fish balls, which Kowloon producers sold to local restaurants.

Sanitation was of minimal importance, Girard says: "It was an intensely difficult place to function, with no laws governing health or safety."

Law enforcement typically only intervened for serious crimes, Girard says, though rumors were always swirling that Hong Kong's government preferred to turn a blind eye.

One law that was consistently enforced: The Walled City could be no higher than 13 or 14 stories. Otherwise, low-flying airplanes would have trouble meeting the nearby runway.

Despite its seedy reputation, the Walled City offered a sense of togetherness to thousands of people who had no community, Girard says.

"Its physical reality kind of belied this community that it was," Girard says, adding that people's attitudes toward him changed around 1990 when they learned the structure was to be knocked down.

People began living increasingly quiet, traditional lives. Though he entered as a threatening outsider, Girard eventually left having formed genuine relationships.

After the city was torn down in 1994, the country built a park in its place. Today, Kowloon Park attracts photographers, birdwatchers, and tourists looking for a relaxing trip through scenic Hong Kong — with plenty of room.

"Hong Kong is kind of a surreal place," Girard says. "The Kowloon Walled City was one of its more surreal mutations, but Hong Kong evolves and Kowloon evolves."

You can find more of Girard's photographs of Kowloon Walled City, as well as images and essays from photographer Ian Lambot, in the book "City of Darkness: Revisited."