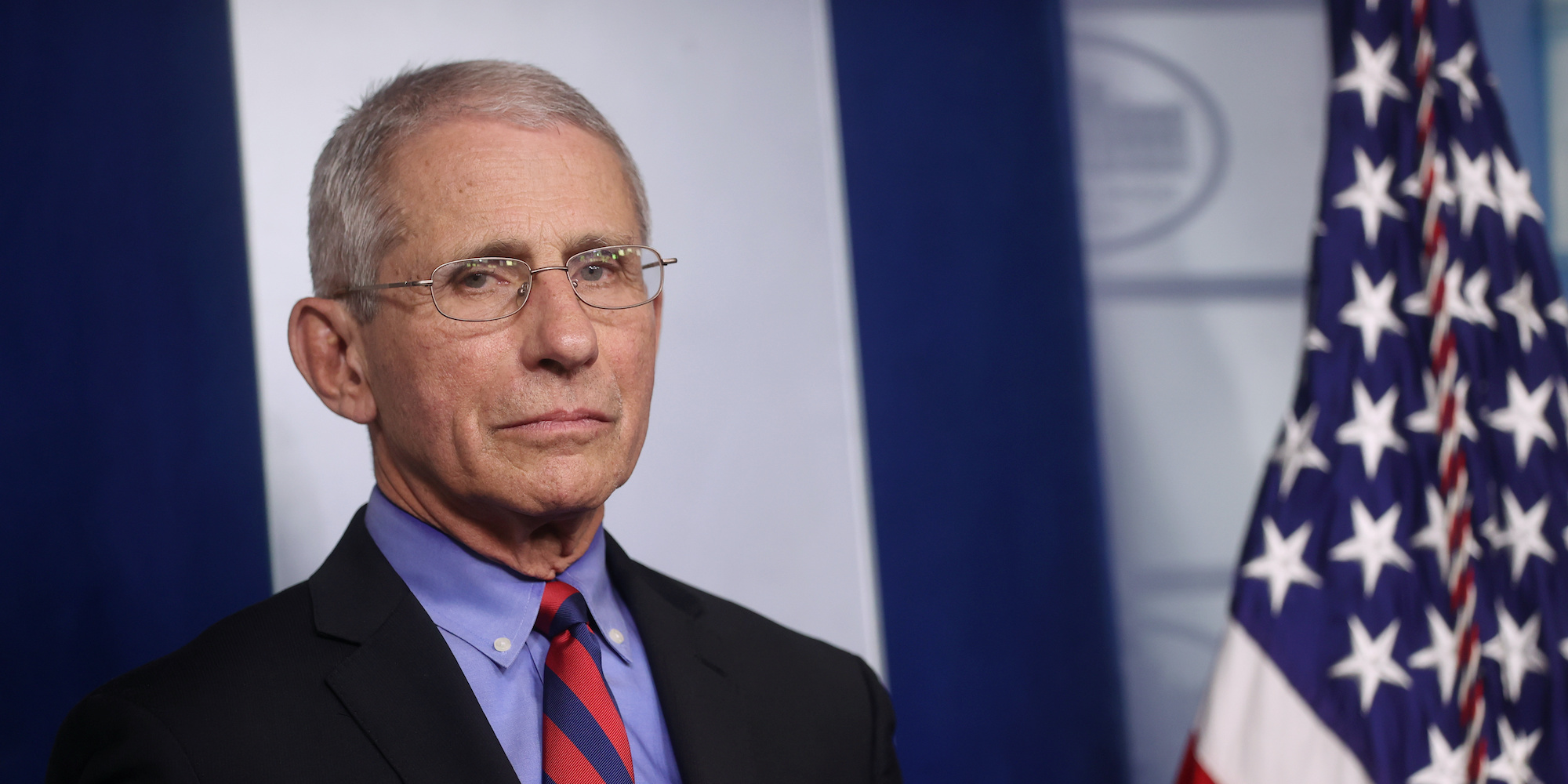

- Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, said the earliest the US may get a coronavirus vaccine will be in 12 to 18 months.

- Some experts say reaching that target may be challenging, because vaccines require a lot of testing.

- One worry is “immune enhancement,” normally spotted in animal testing, whereby a vaccine actually weakens a person’s response to the virus.

- It can take 10 years or more to bring a vaccine from the starting block to being approved by regulators. The FDA says, in this case, it will be flexible to accommodate approval for a workable COVID-19 virus vaccine.

- 40 vaccines for the coronavirus are in development right now, according to the World Health Organization. A number of labs have begun human trials.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

After US Health Secretary Alex Azar said a coronavirus vaccine candidate had been developed in three days, with a clinical trial already in the works, Dr. Anthony Fauci, the top infectious diseases advisor to the White House, sought to temper his enthusiasm.

Fauci, director of the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, said that the earliest the US could possibly get a vaccine would be in 12 or even 18 months – “at least.”

Even a year-and-a-half would be staggeringly fast for vaccine development, and some experts have voiced concerns that a vaccine produced on that timeline could hurtle too quickly through safety trials.

Despite efforts to stop the spread of the virus with social distancing, the only way to definitively prevent more deaths and allow society to get back to normal, is with a vaccine. The US, the country worst affected by the coronavirus, with 188,592 cases and 4,056 deaths as of Tuesday night, is spearheading efforts to develop one.

Scientists already have a head-start, thanks to years research on potential coronavirus vaccines, but there are still plenty of necessary obstacles. One of the most pertinent is that some of the most prominent candidates for a coronavirus vaccine are using novel technology that has never been used in an approved vaccine.

"When Dr. Fauci said 12 to 18 months, I thought that was ridiculously optimistic," Paul Offit, the co-inventor of the rotavirus vaccine in the late 1990s, told CNN. "And I'm sure he did, too."

Scientists have spent years preparing for a coronavirus vaccine

Vaccines can take 15 to 20 years to get from inception to approval, Mark Feinberg, CEO of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative, told STAT News. They have to be tested in the lab, then in animals, before being tested for safety in a small group of people. After that, they're tested in more people to see if they can prevent a disease.

For example, vaccines for other kinds of coronaviruses that caused two recent deadly epidemics - MERS and SARS - took longer than 18 months to develop, and neither have made it all the way through the approval process.

After severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) broke out in 2003, it took 20 months for a vaccine to be trialed on humans. The outbreak had subsided by that time, and a vaccine was under development until 2016, and was ultimately put on hold.

Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) broke out in the Arabian Peninsula in 2012, and spread to South Korea in 2015. There is still no approved vaccine, as the outbreak died down before serious testing.

Despite plenty of funding for vaccine development early on in the MERS and SARS epidemics, momentum waned as the outbreaks were brought under control, and they were ultimately shelved.

"For a new coronavirus vaccine to be available for large populations, I would say it's a matter of two years minimum," Dr. Stanley Plotkin, professor emeritus at the University of Pennsylvania, who has worked in vaccine development since the 50s, previously told Business Insider's Andrew Dunn.

Work on Ervebo, a vaccine developed for the Ebola outbreak, started in 2014 during an outbreak in West Africa that spread to other countries, including the US. Though the outbreak was contained, more outbreaks in the years after kept momentum up, and Ervebo was approved by the European Commission and the US Food and Drug Administration in 2019.

One upside for scientists working on a vaccine for COVID-19 is that the novel coronavirus (technically called Sars-CoV-2) shares 80% to 90% of its genetic makeup with Sars-CoV, the virus that caused the 2003 SARS outbreak, according to the Guardian.

This means companies like Novavax, based in Maryland, can repurpose the technology they were using to make SARS and MERS vaccines for the novel coronavirus.

Animal testing is an important stage to spot potential safety problems

Some scientists worry that a rushed vaccine could result in what's known as "enhancement" whereby a vaccine actually weakens a person's response to a virus when they contract it. For example, one study on a SARS vaccine in 2004 found that some ferrets developed hepatitis, rather than a resilience to the coronavirus.

"I understand the importance of accelerating timelines for vaccines in general, but from everything I know, this is not the vaccine to be doing it with," Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at Baylor College of Medicine, told Reuters.

"There is a risk of immune enhancement," Hotez added.

"The way you reduce that risk is first you show it does not occur in laboratory animals." But in the rush to find a vaccine to the coronavirus, some developers are skipping animal trials, Stat News reported.

Some vaccines are already in development, but 'not all horses will finish the race'

Around 40 vaccines for the coronavirus are in development right now, according to the World Health Organization.

But Bruce Gellin, head of the global immunization programme at the Sabin Vaccine Institute, said that doesn't mean we will get 40 working vaccines.

"Not all horses that leave the starting gate will finish the race," Gellin told the Guardian.

Gary Kobinger, a virologist at Canada's Laval University, told the New Scientist magazine: "We could have a vaccine in three weeks, but we can't guarantee its safety or efficacy."

There are, however, encouraging signs that a vaccine may be within reach.

The Massachusetts-based firm Moderna started testing their vaccine on humans in March.

Moderna is using a new, fairly untested, and as yet unapproved method for its vaccine. The technique meant Moderna only needed the genetic information of the coronavirus to get to work on its vaccine, the biotech firm's CEO Stephane Bancel told Business Insider.

Novavax said it hopes to test its vaccine on humans in Spring 2020.

The pharmaceuticals giant Johnson & Johnson has been researching a coronavirus vaccine since February and says it will start human trials in September.

"My people will kill me if I commit to anything earlier than that," Paul Stoffels, J&J's chief scientific officer, told Business Insider when asked about a trial date. "Early September is like warp speed."

The FDA has said it will work to help get a vaccine approved quickly for the coronavirus.

"When responding to an urgent public health situation such as novel coronavirus, we intend to exercise regulatory flexibility and consider all data relevant to a certain vaccine platform," Stephanie Caccomo, an FDA spokeswoman, told Reuters.