- Many K-12 schools are flying blind on how to reopen as President Trump threatens to cut off funding to schools that don’t reopen without providing additional guidance and teachers push back against returning to potentially unsafe conditions.

- The economy can’t recover without open schools, yet students can’t continue to struggle with virtual learning.

- There’s a difficult balance to strike this fall.

- Here are some of the big ideas that have been suggested – and implemented – around the world to allow a return to in-person instruction, from testing to pod-style classrooms to outdoor classes. Some of them are quite weird.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

For many K-12 students, back-to-school season is looming – and it’s going to look a little different this year.

Some schools, like those in New York, are planning on only partially reopening, while some schools in Florida are set to reopen fully, and others in California are planning on remaining remote.

Meanwhile, President Donald Trump has threatened to cut off funding for schools that don’t reopen (something that he doesn’t legally have the authority to do). Trump does have the authority to approve extra funding for schools, which teachers have been saying is badly needed to reopen safely

The Republican “HEALS Act” proposes $70 billion of K-12 education of education, but much of that money is directly tied to reopening. It’s also much less than what would be provided in the bill already passed by the Democratic-led House, but the parties have not so far been able to reach an agreement.

There's a delicate balance to be struck: the economy cannot recover with daycares and schools closed. And experts say that key aspects of in-person instruction can't be replaced with virtual learning. But reopening also must be safe for teachers, students, and families.

Here are some big - and weird - ideas at the forefront of schools reopening, from frequent testing to pod-style classrooms to outdoor instruction.

One intriguing suggestion comes from small-town Germany: students self-administering their own coronavirus tests at school.

In Neustrelitz, Germany, a negative coronavirus test gives students a green sticker - and the freedom to not wear a mask.

As Katrin Bennhold reported for The New York Times, students could voluntarily go to tents at their high school, get a test kit, and swab themselves. One student received results later that night.

Everyone can get two free tests a week. Those who test positive are required to stay home for two weeks. And the negative testers only get green stickers until their next test.

When it comes to scaling, there could be a few issues: Henry Tesch, the school's headmaster, told Bennhold that the tests came from an old friend at a biotech company. He offered them to Tesch as a free pilot. Without that, it would've been a costly endeavor.

And the US is in the midst of another coronavirus testing crisis, as Business Insider's Morgan McFall-Johnsen reported. Tests have grown more difficult to come by, and result wait times can clock in at over a week.

Schools worldwide tried bringing certain age groups back first as a pilot test — and then bringing back everyone else.

In Germany and Wuhan, older students - particularly those who needed to take exams - came back first. As Bennhold reported for the Times, Germany let them return to the classroom first because "they are better able to comply with rules on masks and distancing."

But Denmark took a different approach, with younger students returning first. After rates remained low, older students followed. As Sean Coughlan reports for the BBC, those younger students were kept in "a virtual cocoon," where groups stick together and don't have crossover. As rates remained low, older students began to return.

Another option similar to staggering age groups would be to stagger and shorten schedules— as New York City said it might try.

On July 8, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced the city's 1,800 public schools could reopen in the fall with some modifications. The city's 1.1 million students will continue to learn remotely, but some could attend class up to three days a week.

Classrooms that once typically had 30 people would shrink to 12, including teachers. Individual schools would have to determine which groups of students to bring back at what times, shortening their time in schools and leaning into a hybrid educational model.

On July 31, de Blasio announced that the test positivity rate in the city must remain below 3% for this plan to go ahead. The positivity rate for the city has recently remained below that threshold, but the city will need to maintain it to ensure schools open with their hybrid model on September 10.

Child care centers for essential workers stayed open in New York City in the early days of the pandemic, and were successful in keeping cases low. They used the "pod" method.

NPR's Anya Kamenetz dove into how child care centers for children of essential workers kept both children and families safe. One key element: pods of children.

As Kamenetz reports, YMCAs and New York City facilities created "pods" of up to nine children, all assigned to one adult. In the pods, children didn't wholly observe social distancing - and they didn't wear masks all of the time. And pods stuck together, not playing or learning with other groups.

"These experiences illustrate that it's possible to bring kids together without a guarantee of an outbreak or a serious situation developing," Dr. Joshua Sharfstein told Kamenetz, although, as Kamenetz writes, "they don't guarantee the opposite."

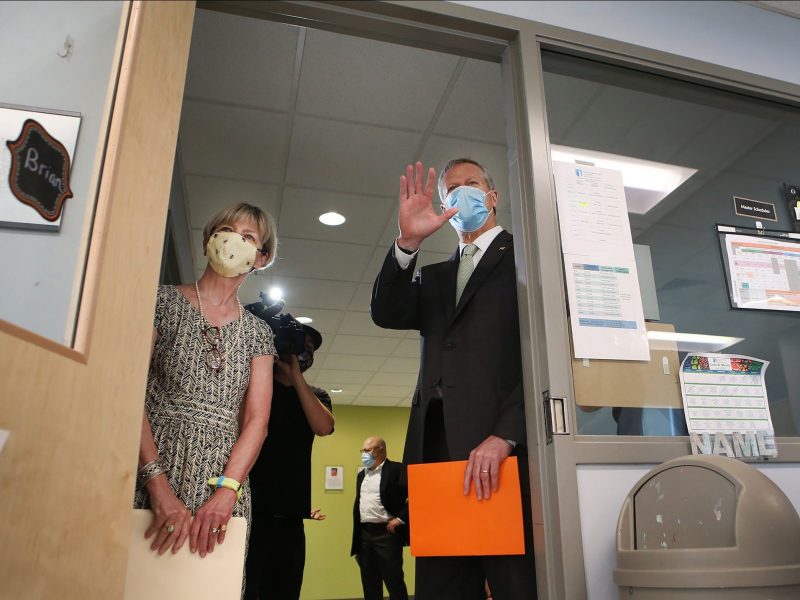

Some schools are debating how much physical distancing is necessary — with Massachusetts deciding three feet would be alright, versus the CDC's recommended six feet.

Massachusetts' initial school guidance came out at the end of June. The guidance noted that the CDC recommends maintaining a physical distance of six feet between individuals, and while that is preferable, a distance of as little as three feat could lead to reduced transmission.

Schools can opt to distance three feet versus six feet. The slightly smaller distance could allow students to feel more connected to their classmates and their instructors. Another idea to increase that connection is opting for face shields over face masks.

Districts are supposed to submit their preliminary plans for approval this week. Some teachers are pushing back on the safety of returning to the classroom.

Other suggestions include using other currently empty spaces for socially distanced classes.

New York Magazine's Justin Davidson suggested using large empty spaces for socially distanced classes - especially in places like New York City, where theaters and auditoriums have stayed untouched since March.

Space like the Javits Center have already been used for makeshift hospital space, and can be just as easily reconfigured to support classes. Convention centers, theaters, auditoriums, and more in other cities could be a solution to having students meet for classes inside.

To skirt the idea of putting kids inside altogether, another idea is outdoor classes.

The outdoor concept is quickly gaining traction because chances of infection are lower outdoors, where the virus cannot thrive, according to a June new study.

In a New York Daily News opinion piece, New York City Comptroller Scott Stringer said moving classrooms outside was a logical decision - almost like restaurants and bars pivoting to outdoor seating. In the city, he noted, nearly 30 million square feet of outdoor space is directly connected to schools, so schools wouldn't even have to resort to setting up camp in local parks and could "maintain easy access to bathrooms, handwashing stations, and cafeterias."

New York Magazine's Adam Raymond pointed out that the idea is taking off elsewhere. One Vermont school plans to hold classes outdoors until Thanksgiving, while other schools in Philadelphia and Knoxville plan to hold some classes outside in the fall.

The Atlantic's Olga Khazan wrote that outdoor classes "might be the answer to America's school-reopening problem," but also noted that an outdoor school day would include much less technology, be subject to the weather, and wouldn't necessarily address a different problem - transportation.