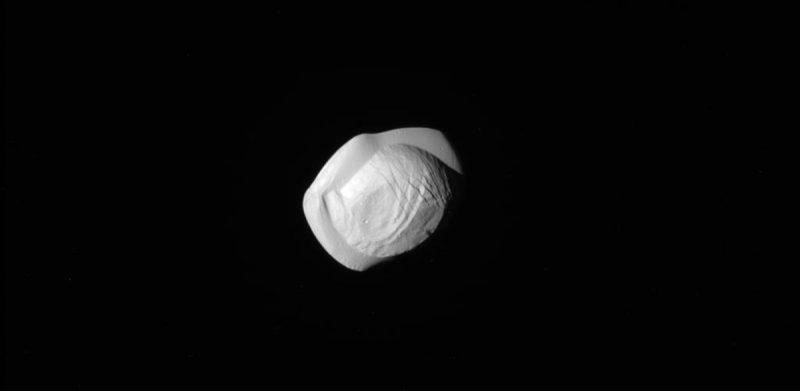

Moons aren’t always round. Some look like walnuts, other like potatoes.

But Pan – a moon of Saturn – has to be the first ravioli-shaped satellite we’ve ever seen.

According to a new post by NASA, these are the closest photos of the object ever taken. The plucky photographer was the Cassini spacecraft, a nuclear-powered robot that has orbited Saturn since 2004.

This top-down image from Cassini – taken from about 15,000 miles (24,500 kilometers) away – shows what may be the sharpest view of the moon:

Precious little is known about Pan.

What we do know is that it's one of Saturn's 62 known moons, and it's located some 950 million miles from Earth. The icy object is about 16 miles (26 kilometers) across at its widest part, and 8.8 miles (14.1 kilometers) wide on average.

Plopped onto a map of the United States like a giant piece of pasta, it could mostly cover the five boroughs of New York City.

The reason it's shaped like a round ravioli is a mystery, but it may be because of radioactive elements that it gobbled up during its formation. Stuck inside Pan, those warm elements may have led to a gooey center, which - if it spun quickly when it was young - may have flattened out the satellite, much like Saturn's moon Iapetus.

Voyager 2 (another nuclear-powered probe) photographed Pan for the first time in the 1980s, but astronomers didn't find the moon in those images until 1990.

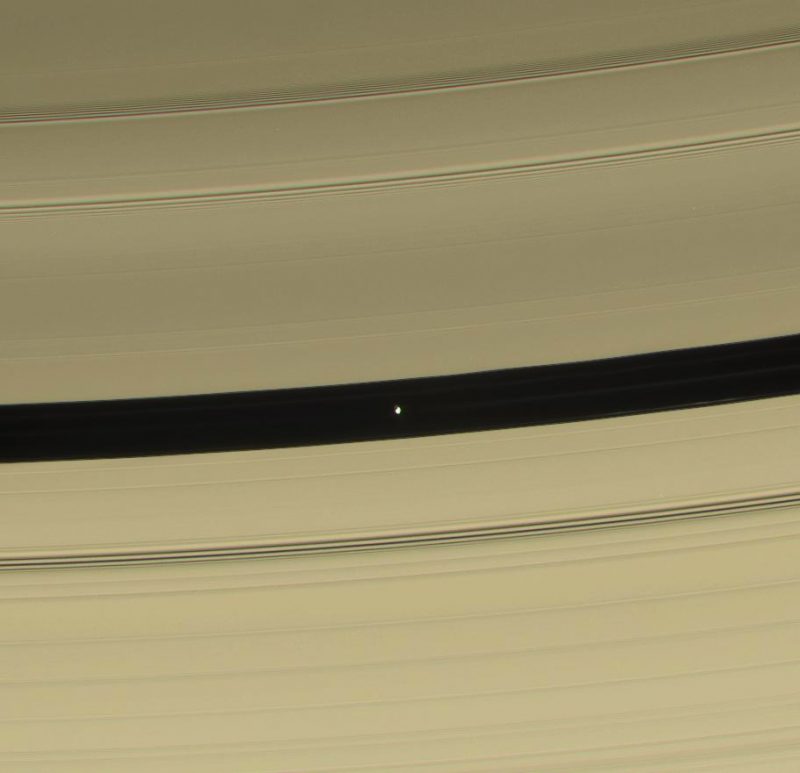

Years later, Cassini's photography showed Pan had scrubbed a 200-mile-wide lane in Saturn's expansive rings over the eons, a feature called the "Encke Gap".

Unfortunately, these incredible shots of Pan and other moons, like Daphnis, will be among Cassini's last.

NASA recently fired Cassini's thrusters to put it on course for a "Grand Finale" orbit, allowing the robot to take in these unprecedented views.

But sometime in late April, Cassini will burn more fuel to begin a months-long death spiral. The probe will swoop over Saturn's north pole, slip between the planet and its rings 22 times, and ultimately "burn up like a meteor" on September 15, 2017, according to NASA.

And why, you might ask, end the mission in a flame-out instead of letting Cassini carry on, like the Voyager spacecraft, which continue their drawn-out escape from the solar system?

Because two icy moons of Saturn, Enceladus and Titan, are dripping with water and thus are promising places to look for life - so NASA wants to avoid any chance that Cassini would crash into them and contaminate the worlds with any earthly germs.