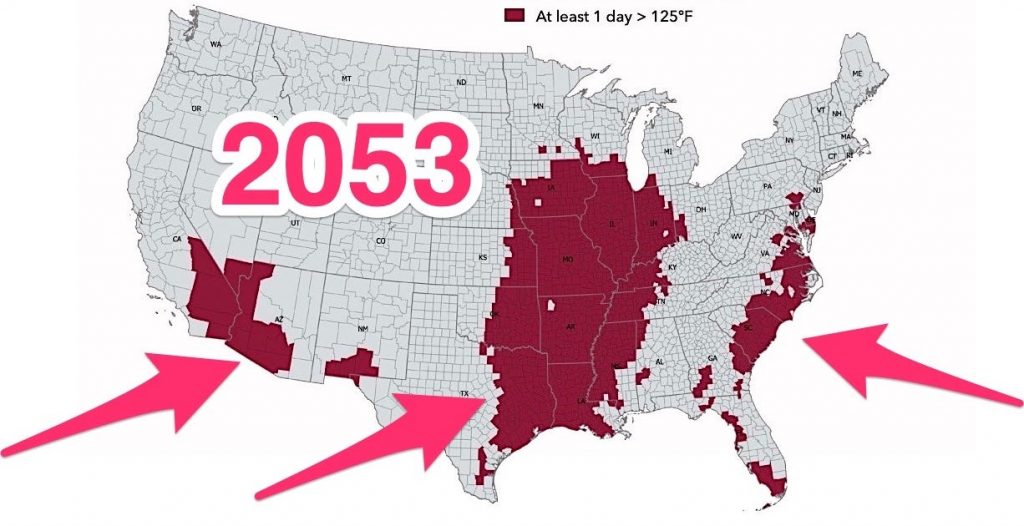

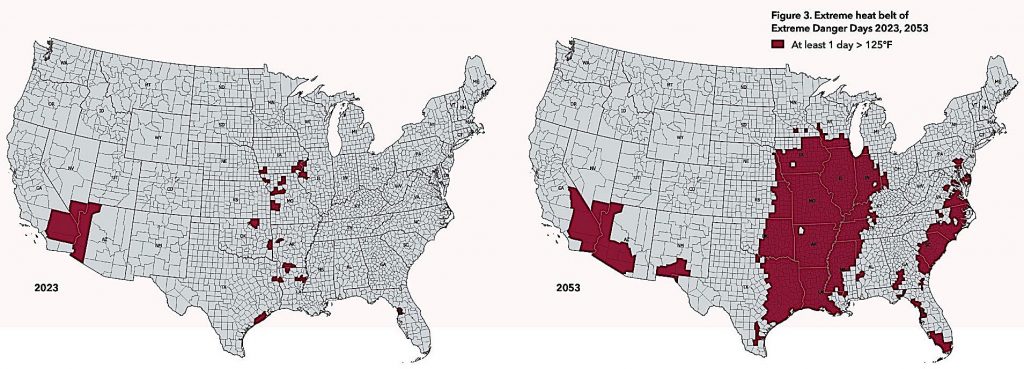

- An "extreme heat belt" may form in the US by 2053, an analysis from First Street Foundation predicts.

- The report used satellite data to model heat risk at the property level for the next 30 years.

- Predictive maps show that 107 million Americans could see temperatures above 125 degrees Fahrenheit.

The heat waves scorching the US this summer may just be the beginning of an extreme heat belt forming across the country.

"If people think this was hot — this is going to be one of the better summers of the rest of their lives," Matthew Eby, CEO of the climate-risk research nonprofit First Street Foundation, told Insider.

The foundation published a "Hazardous Heat" report on Monday, using a peer-reviewed model to assess six years of US government satellite data and predict future risk of extreme heat by property. Its conclusions align with scientists' warnings that extreme heat will become more common, more extreme, and longer-lasting in the coming decades.

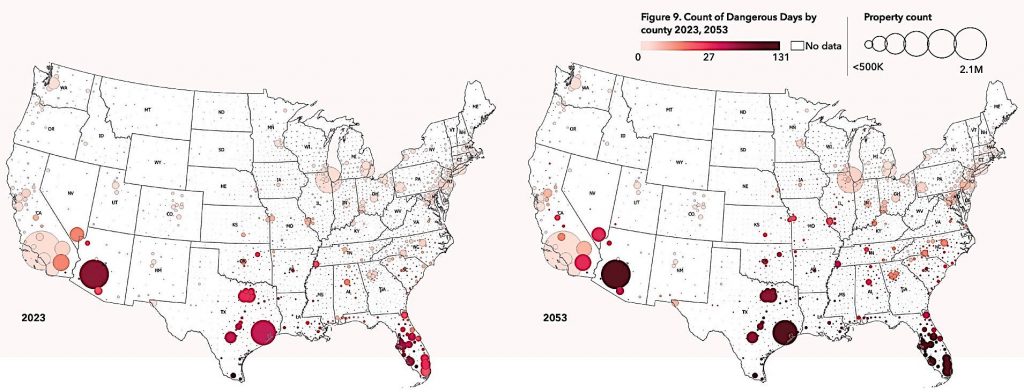

Next year, the report projects that 8 million Americans face the prospect of sweltering in at least 125 degrees Fahrenheit for at least one day. By 2053, that would rise to 107 million Americans — 13 times more people in just 30 years, according to the report.

That's about one-third of the current population, covering one-quarter of the US land area, as shown in the map below.

The majority of that extreme heat is expected in the center of the country, from the Texas and Louisiana Gulf Coast up through Chicago — an area that First Street Foundation is calling the "extreme heat belt." Significant portions of the southwest and southeast are also likely to have more than one day above 125 degrees Fahrenheit in 2053, according to the report.

At such high temperatures, the National Weather Service warns that risk of heat stroke is high. Infrastructure often fails at such high temperatures, too. Roads buckle, train tracks bend and can cause derailing, and airport tarmacs can melt and prevent takeoff. Sometimes the power even goes out.

More hot days and more heat waves

Days that breach 125 degrees Fahrenheit aren't the only ones to worry about. Even temperatures above 100 degrees can be dangerous. In another map, below, the report projects more days above 100 degrees across the southern half of the country.

The extreme heat of the summer so far in 2020 lines up with many of the locations where First Street Foundation expects the most heat in years to come, Eby said.

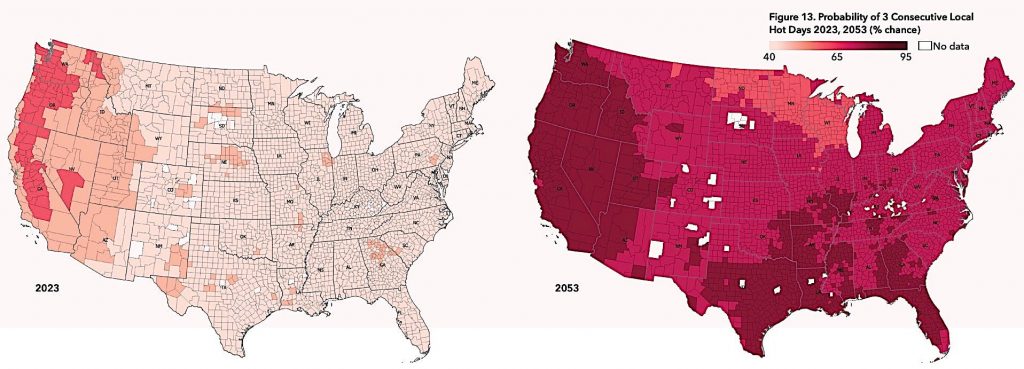

For example, as the map below shows, the report projects more heat waves across the country, with significantly increased risk in northern areas including the Pacific Northwest, and other regions that aren't historically accustomed to extreme heat.

The projections in this report are conservative, since it assumed a future scenario where humans drastically cut the greenhouse-gas emissions that are driving climate change and increasing global temperatures.

If the world doesn't cut emissions soon — particularly through a rapid transition away from fossil fuels to clean energy — the future of extreme heat could look even worse than the maps in this report.

"If anything, our undercuts or our underrepresentation of these heat impacts will be noticed in 30 years," Eby said.

Even if humans stop emitting greenhouse gases tomorrow, some heating is locked in by the gases we've already added to the atmosphere. To protect life, infrastructure, and property, Eby said, individuals and companies and governments have to prepare for more extreme heat in the future.

"Our hope is that this data can inform everyone from the individual, to commercial users to state, local and federal governments, which are all users of our data," he said.

Their data is publicly available on riskfactor.com, where you can check past data, as well as current and future risks for individual properties.