The Federal Reserve is not expected to raise interest rates again until at least December, and even that increase is now in doubt given low inflation and high political uncertainty in the United States.

That doesn’t mean the central bank has no plans to tighten monetary policy, however. Officials are widely expected to announce the start of a gradual reduction of the Fed’s $4.4 trillion balance sheet, which more than quintupled in response to the Great Recession and financial crisis of 2007-2009.

Policymakers are hoping the shrinkage, which they intend to accomplish by ceasing reinvestments of maturing bonds back into the central bank’s portfolio, will have minimal market impact. But a previous episode in 2013 known as the “taper tantrum,” when bond yields spiked sharply higher at the mere mention of a possible end to the Fed’s bond-buying program, offers a cautionary tale.

Regardless of immediate market impact, there will be a longer term effect on the government budget, currently the subject of heated debate, that most investors and politicians are ignoring.

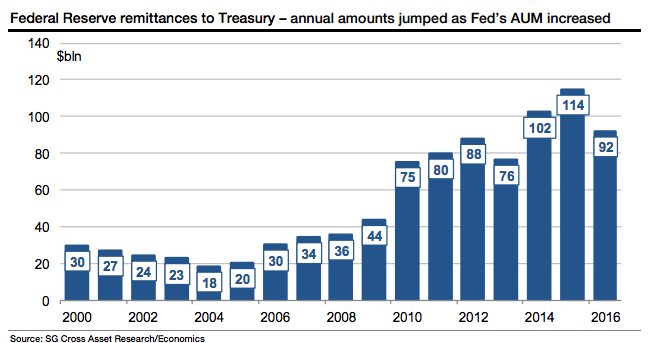

That’s because the Fed’s bond-buying program, in addition to lowering the government’s borrowing costs at a time when weak economic activity called for bigger budget deficits, created a stream of yearly returns of nearly $100 billion for the Federal Reserve which it then siphoned back to the Treasury.

Sometimes these are referred to as the Fed's "profits," but that is a deceptive way of describing what is in effect an intra-government transaction.

"As assets under management drop, so too will revenue on that portfolio. This will be a lost revenue source for the Treasury that will raise deficits and add to the Treasury's financing" costs, writes Societe Generale Economist Stephen Gallagher in a research note to clients.

President Donald Trump recently struck a surprise deal with Democrats to push back the debt ceiling another three months that seemed to alienate his own Republican allies, complicating an already strained economic agenda. The Fed's shrinking balance sheet only serves to narrow the president's perceived fiscal wiggle room.

As the Fed's portfolio expanded during the recession, so did remittances to Treasury, which jumped nearly fourfold from the $25 billion average that prevailed before the crisis and concomitant expansion in reserves. The unwinding will bite.

"The reduction from recent years will add to the deficit," Gallagher says, as the chart below suggests.

"As the Fed's portfolio shrinks, deficits and financing needs rise the Fed's portfolio and income on that portfolio offset funding needs that would normally be met in the private market," Gallagher said.

"As the Fed shrinks its Treasury holdings, a greater financing need will burden private investors," he added. "In addition, the reduced revenue could cut the amount of remittances by $50 billion to $75 billion a year, implying an increased deficit of $500 billion or more over a 10-year time frame. This increase will need to be financed via new Treasury issuance."

They estimate that a reduction of $2 trillion over time, within the very large ballpark of what the Fed has signaled it will do, would cost Treasury around $40 billion in revenue, the strategists say. Still, SocGen has "reason to believe the amount would be greater," because the average maturity of bonds in the Fed's possession will also go down over time.