Claggett Wilson isn’t exactly a household name, but his battlefield watercolors are getting buzz at a big new exhibition of World War I and American Art.

“[Wilson’s] watercolors of exploding shells and mad-eyed soldiers are standouts in an exhibition rich in intensely original work,” Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times.

“I was most moved … by an artist I had never heard of: Claggett Wilson,” Thomas Hine wrote in the Philadelphia Inquirer. “The works vary a good deal in style … [but] what they share is immediacy and intense emotion.”

“These are incredible,” Slate’s Amanda Katz tweeted in response to a series of Wilson works tweeted by her colleague Rebecca Onion.

The exhibition, which includes Wilson works not publicly exhibited since the 1920s, is at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts through April 9 before moving to New York and Nashville.

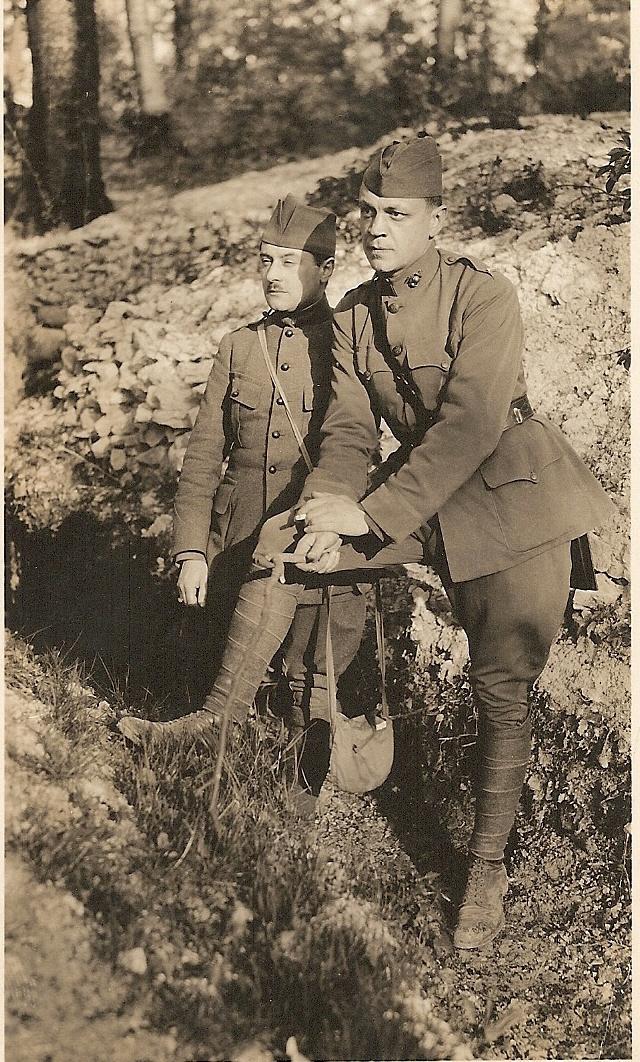

Wilson was one of the few American artists who saw combat in the war. He was one of even fewer who was on the battlefield as a soldier, serving as a second lieutenant in the Marines and winning a citation for bravery under fire.

Historian David Lubin, who is one of the curators and the author of "Grand Illusions: American Art and World War" (and this reporter's father), says Wilson's artistic contributions were unmatched in America. He writes: "World War I did not produce an American artist of [German painter Otto] Dix's brilliance and depth, but Claggett Wilson was the closest equivalent."

Although critically acclaimed, Wilson's works didn't sell well initially and were left to languish for decades in storage. As one 1935 article declared, "Like the bursting of a shell, an arresting brilliance, then silence, is the fate of these paintings which were once considered America's most ambitious contribution in art to the memory of the Great War."

With permission from PAFA, we're running a set of works by Wilson below.

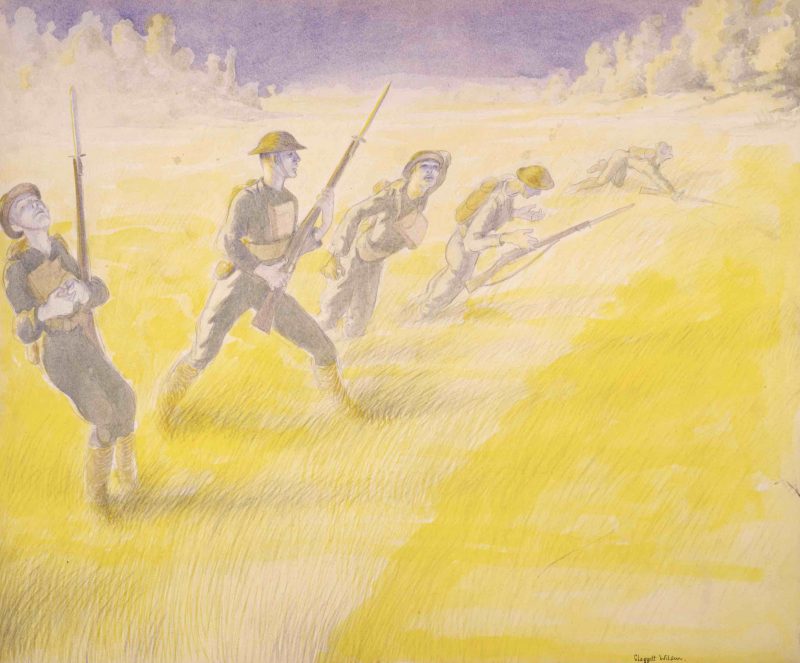

Wilson's dreamlike painting of Marines at Bois de Belleau shows the beginning of one of the deadliest battles in the history of the Corps.

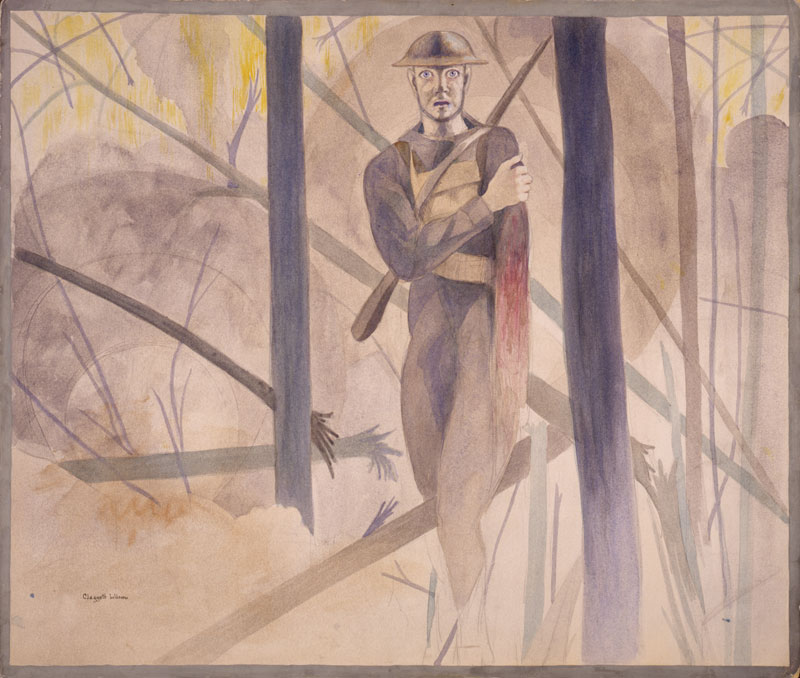

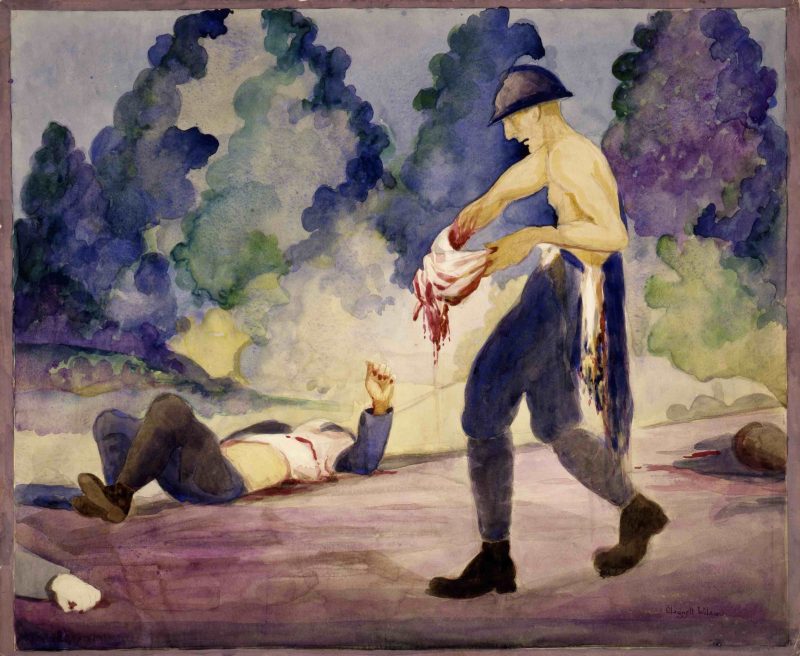

Wilson himself was gassed during the battle and found himself stranded in no man's land for three days. Here's his painting of another shell-shocked soldier.

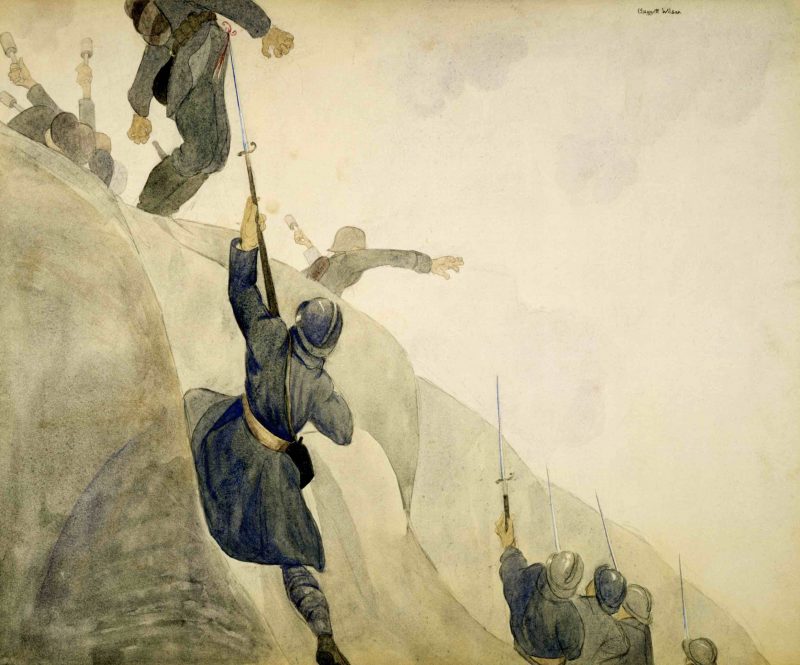

Another work from Bois de Belleau shows wounded French troops retreating.

Wilson's works are hard to categorize. This painting of an explosion resembles abstract expressionism, but it's grounded in reality by the poor figures in the corner.

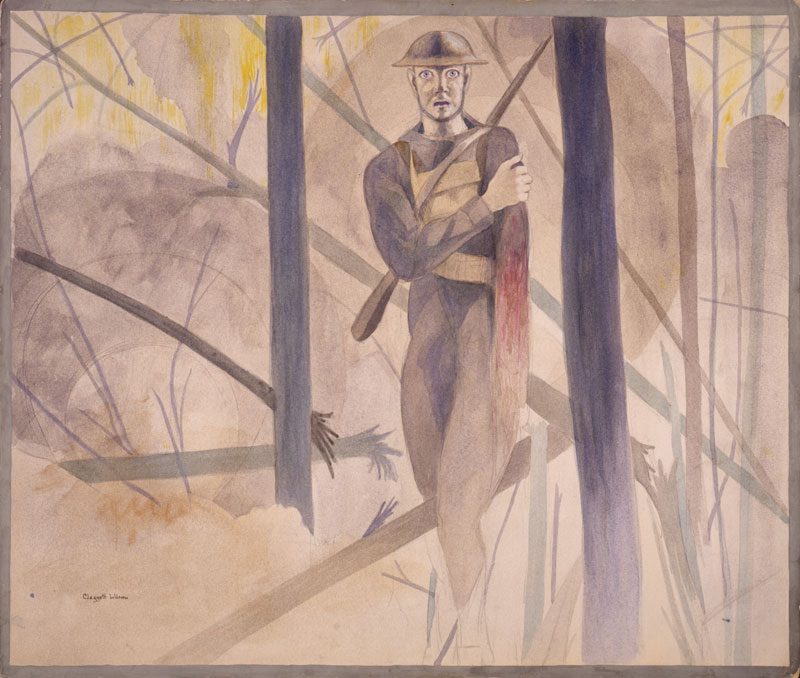

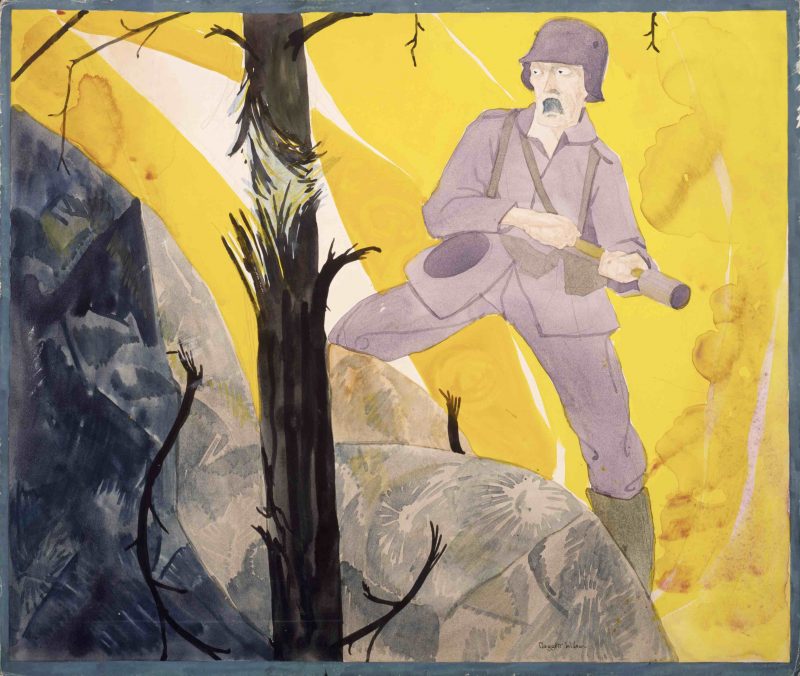

Wilson often painted exaggerated facial expressions, drawing inspiration from traditional Japanese art and theater—as in this painting of a German grenadier shocked as a concussive force shatters the tree in front of him.

Critics have pointed to works like "Front Line Stuff" as "pure cinema."

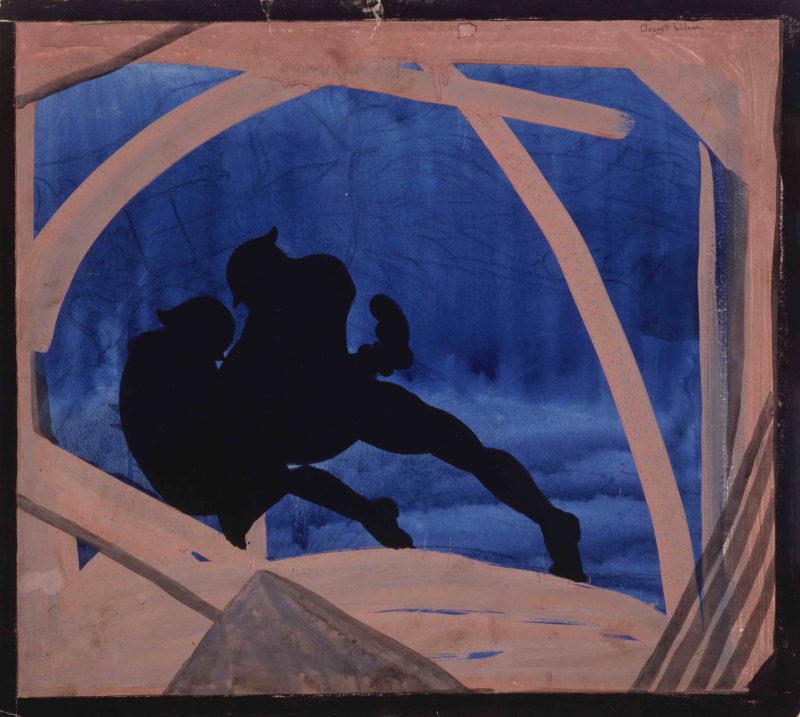

Other works were theatrical, like an "Encounter in the Darkness" framed by the ruins of a farmhouse.

Some works showed the bleak absurdity of war, like the "Dance of Death" of German soldiers caught in barbed wire.

Wilson was in his early 30s when he joined the Marines. Before that, he had studied with modernists in New York and Paris and taught at Columbia University's progressive Teachers College.

Wilson's battlefield works, notes the catalogue, are "harrowing and sometimes hallucinatory watercolors that call attention to the loneliness and despair of soldiers on the front lines ... [that] depicted his former adversaries, German foot soldiers, as fellow victims of the collective insanity of war."

Source: "World War I and American Art"