- China’s new natural security law is the latest challenge for universities as classes pick up again.

- Universities like Princeton and Harvard are worried that under the new law students may be prosecuted in China for expressing dissenting political opinions even if they’re not in the country, The Wall Street Journal reported.

- The new national-security law stemmed from the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong and allows China to find and prosecute people for “sedition, subversion, terrorism, and colluding with foreign forces.”

- Professors are placing warnings on classes or implementing new forms of grading to help protect students.

- Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

Universities like Princeton and Harvard are grappling with another obstacle as classes go back in session: China’s new natural security law that could prosecute individuals for dissenting political opinions even if they’re not in China, The Wall Street Journal reported.

Some classes at universities will come with a label “This course may cover material considered politically sensitive by China,” and students at Princeton would use code names to protect their identities when submitting work, The Journal reported.

The new national-security law stemmed from the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong but extends far beyond it. The law allows China to find and prosecute people for “sedition, subversion, terrorism and colluding with foreign forces,” Business Insider previously reported.

In order to mitigate the risk this could have to students and faculty, both Chinese and American schools have adopted different measures. The Journal reported that Harvard Business School could excuse students worried about the risk of prosecution from discussing politically sensitive topics.

In the 2018-2019 school year, more than 370,000 Chinese students and around 7,000 students from Hong Kong were enrolled in US colleges, and many chose to take courses on Chinese politics, academics told The Journal.

"We cannot self-censor," Rory Truex, an assistant professor who teaches Chinese politics at Princeton told The Journal. "If we, as a Chinese teaching community, out of fear stop teaching things like Tiananmen or Xinjiang or whatever sensitive topic the Chinese government doesn't want us talking about, if we cave, then we've lost."

Truex, like other several other professors, has introduced blind grading, where students hand in assignments with a code instead of their actual name so their views can't be linked back to them.

Professors are not just worried about Chinese citizens taking these classes and potentially being implicated, they're also worried about themselves, and others who might visit the country later on.

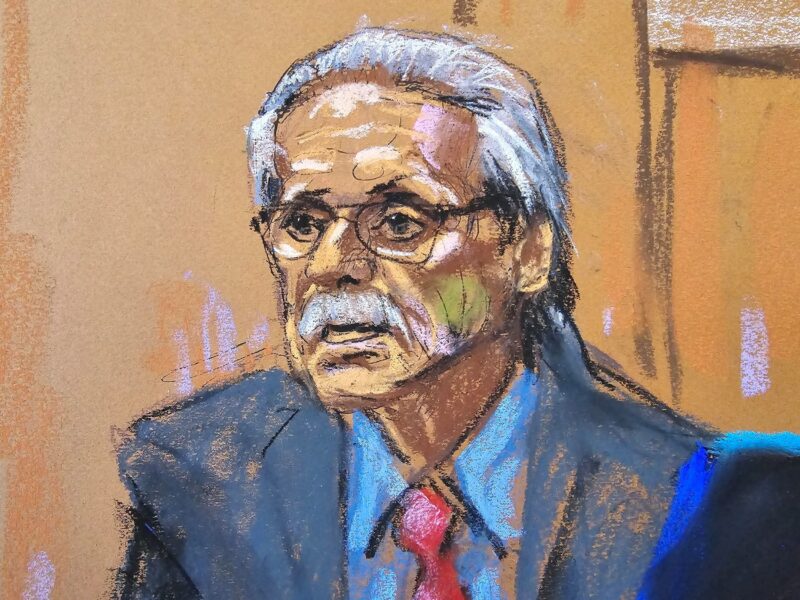

Earlier this month, Business Insider reported that Samuel Chu, who is a naturalized US citizen from Hong Kong was put on a list of fugitives by China for lobbying Congress to punish China limiting Hong Kong's autonomy.

"China has always been hostile to Western journalists and academics, and this amps it up," Truex said.

Avery Goldstein, a professor in the political science department at the University of Pennsylvania, said he's putting a warning on his course of the risks before students enroll because a security breach could put them at risk.

"We have to leave it up to the students whether they enroll because it is ultimately their lives that are going to be affected," he told The Journal. "I will make it clear that there is nothing I can do to protect them."