- A jury convicted Ghislaine Maxwell on five of six sex trafficking charges on Wednesday.

- The prosecution's narrow focus and powerful testimony from victims helped lead to a guilty verdict.

- Increased pressure on the jury to return a verdict amid the COVID-19 surge might have played a role.

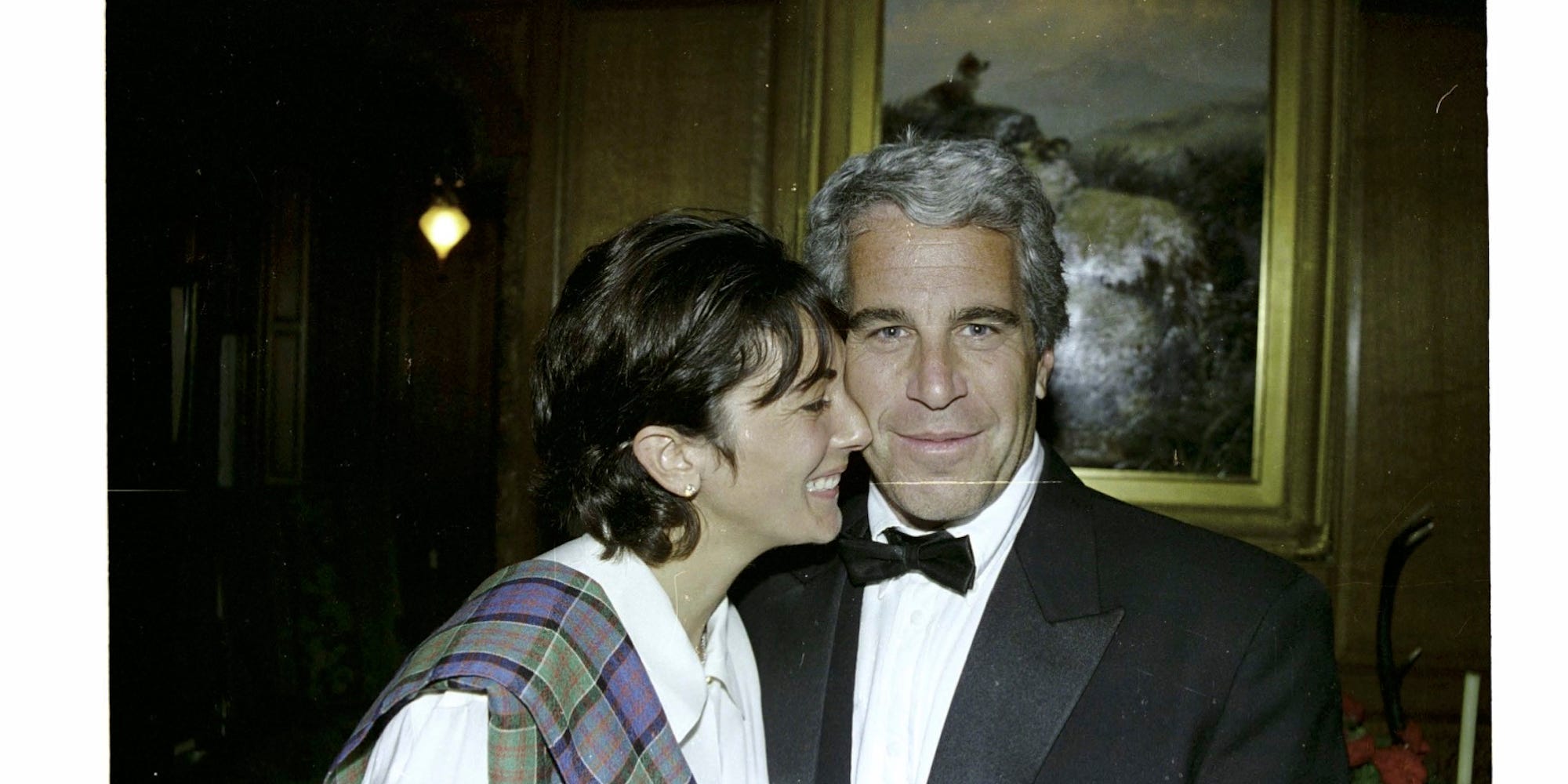

After more than five days of deliberations, a jury on Wednesday found Ghislaine Maxwell, the longtime associate of convicted pedophile Jeffrey Epstein, guilty of five of six sex trafficking charges.

Maxwell was found guilty on three conspiracy charges, as well as a separate sex trafficking count and a charge for transporting a minor to engage in illegal sexual activity. The Epstein associate was acquitted on one charge of enticing a minor to travel to engage in illegal sexual activity.

Although Epstein's and Maxwell's crimes have garnered massive publicity and stoked widespread vitriol, a guilty verdict wasn't guaranteed. The decades-old accusations — they all concerned conduct between 1994 and 2004 — meant that prosecutors had a limited amount of documents that could corroborate each accusers' claims, and the defense was quick to suggest victims' memories may have been distorted by time.

Judge Alison Nathan weeded out jurors familiar with Epstein and Maxwell to avoid possible bias.

Maxwell's attorneys recruited Elizabeth Loftus, a renowned academic of memory and psychology, to testify about how they can be changed and manipulated over time. In closing arguments, they said that jurors couldn't trust the accusers alone, and claimed that prosecutors simply hadn't brought enough evidence to prove Maxwell was guilty beyond a reasonable doubt.

In spite of the defense's best efforts to sway jurors, the overwhelming strength of the prosecution's case, as well as some judicial help, explain how Maxwell was ultimately found guilty.

The Prosecution kept the case narrow

Rather than make the case about the vast number of Epstein accusers — which numbered at around 160 according to a victims' compensation fund established by his estate — the prosecutors focused on specific allegations about Maxwell.

A woman who testified under only her first name, Carolyn, was one example. In order to convict Maxwell on one of the sex-trafficking counts, jurors needed to find that Maxwell knowingly "recruited, enticed, harbored, transported, provided, or obtained" Carolyn to participate in commercial sex acts. It doesn't matter whether Carolyn actually traveled across state lines for the purposes of this charge, only that part of the commercial activity involved multiple states.

Prosecutors kept their evidence for that simple. Carolyn testified that Epstein paid her for sex and said he mailed her a package of Victoria's Secret underwear from New York to her home in Florida. Prosecutors later introduced FedEx records showing that the underwear was mailed from Epstein's Manhattan office where Maxwell was working the day they were sent.

Annie Farmer's testimony was a slam dunk

Annie Farmer was the fourth and final accuser to testify in the trial. Unlike the other three women, whose stories were marked by sexually abusive encounters that stretched over years, Farmer's was much simpler and easier to prove. In 1994, she had two encounters with Epstein. Maxwell was involved in one of them, where she massaged her breasts and egged her on to massage Epstein's feet.

Farmer has told the same story multiple times in legal filings and to journalists and remained consistent. She also kept a diary at the time, where she wrote about her confused feelings about the encounters with Epstein. The relative simplicity of her testimony meant that Maxwell's attorneys had little to work with on cross-examination. It was also instrumental in proving the conspiracy charges against Maxwell.

The judge allowed parts of Epstein's "little black book" into evidence

Before the trial began, Maxwell's attorneys fought vociferously to block prosecutors from entering Epstein's "little black book" into the trial. The book contained contact information for hundreds of people in Epstein's life, including his rich and powerful friends. Maxwell's attorneys argued that prosecutors couldn't sufficiently prove the copy of the book they wanted to enter into evidence was linked to Maxwell personally and that it hadn't been tampered with.

In the end, Nathan permitted a handful of pages to be entered into evidence. The pages showed that phone numbers for some of the accusers in the trial were listed under "Masseuses" and that it had phone numbers for their parents as well.

The pages made clear what the prosecutors had argued all along: That getting a "massage" was just Epstein and Maxwell's code word for sex. Prosecutors successfully highlighted the unlikelihood that Epstein, a wealthy businessman, would be hiring teenage non-professionals to give him massages.

"Use your common sense, ladies and gentlemen," Assistant US Attorney Alison Moe said in closing arguments. "When you call a masseuse, you don't need to call their mom and dad."

The COVID-19 surge put jurors on the clock — which likely helped the prosecution.

Jurors began deliberating in the late afternoon on December 21, following a marathon day of closing arguments from prosecutors and defense attorneys.

"Frankly, I expected a verdict before Christmas, Neama Rahmani, president of West Coast Trial Lawyers and a former federal prosecutor told Insider. "I said, if this drags past the new year, we very well may be looking at a hung jury," he added.

It also looked as though a 2022 return was increasingly likely as jurors worked through the complex charges, writing in a Tuesday note that they were "making progress" but giving no indication that a verdict was forthcoming.

But on Wednesday, Nathan told jurors that she wanted them to sit every day until they reached a verdict, even if that meant deliberating through the weekend and on New Year's Day. Nathan cited the "astronomical" spike in coronavirus cases in New York and the risk of a mistrial should jurors fall ill.

"Put simply, I conclude that proceeding this way is the best chance to both give the jury as much time as they need and to avoid a mistrial as a result of the Omicron variant," Nathan said.

The courthouse, in downtown Manhattan, was originally scheduled to be closed on Thursday and Friday for New Year's until Nathan said she wanted the jurors to continue meeting.

The expedited timeline likely played in the prosecution's favor, Rahmani said, as any holdouts were encouraged to make a final decision.

"As soon as she said you're going to keep going, lo and behold, they reached a verdict," he said. "This is a reflection of them wanting to get this done before the end of the year."